Making sense of our connected world

From theory to practice and back again: A journey in public interest AI

In our research group on public interest-oriented AI, we don’t just talk about the theory; we take a practical approach, developing technical prototypes. One of these is Simba, our tool that automatically simplifies German-language texts online. In this blog post, we reflect on our initial thoughts on public interest AI using our experiences from developing Simba.

What’s what

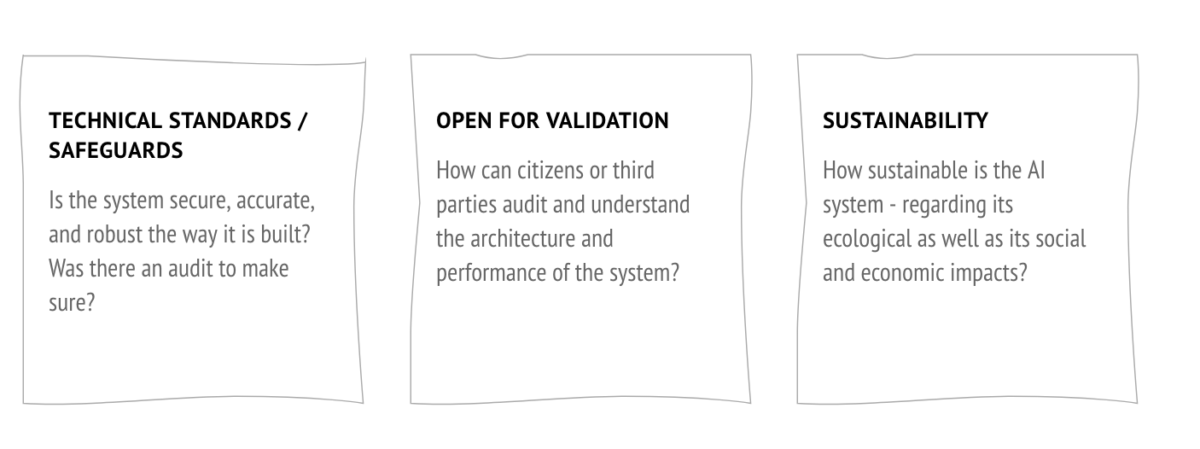

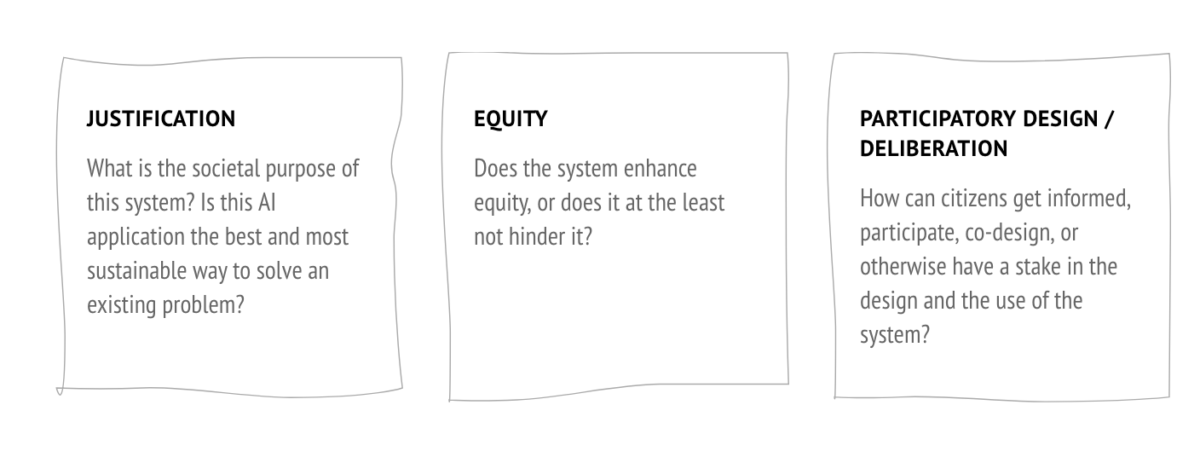

Simba features two AI-supported tools designed to help users better understand German-language online texts. The first is an internet app that simplifies self-authored content, while the second is a browser extension that automatically summarises texts on websites. Both utilise an AI-based language model to automatically simplify German-language texts. Simplification is the act of reducing complexity while still maintaining the core message; it involves replacing longer words with short synonyms, shortening sentences or inserting additional information to make relations between concepts clearer. We have been developing Simba against the backdrop of our six public interest AI principles. These principles were formulated at the beginning of our research project and include the criteria of “justification”, “equity”, “participatory design/deliberation”, “technical standards/safeguards”, “open for validation” and “sustainability”, which are described in the image below.

But first: Why?

“Why” is an important question to ask in the context of public interest AI, reflected in the principles justification and equity. Does the system have a societal purpose that does not hinder equity?

The societal purpose of simplified language is to give as many different people as possible access to the same information. According to the LEO study, conducted by the University of Hamburg in 2018, around 12% of German-speaking adults in Germany have low literacy skills, which means they are capable of reading and writing simple sentences at most. The target groups for simplified language range from people with cognitive disabilities to non-native speakers, children and non-experts. While we still maintain that certain processes themselves could be systematically simplified – particularly in a bureaucratic context – we believe that providing as much information in simplified language is beneficial for a democratic society and contributes to promoting equity.

An AI-based tool could improve efficiency and support translators in providing a wider range of simplified information. Our research has revealed that the websites of public administrative bodies, educational institutions and scientific institutes often exclude a substantial portion of the population from accessing vital information due to their complex language.

Let’s get technical

Technical knowledge is required to develop an AI-based tool – to ensure that the tool is successful, that no unnecessary risks are created and that resources (such as time and money) are not wasted. These points are reflected in the technical standards condition. As a small team, we are reliant on technology made by other players – Simba is based on a large language model from Meta called Llama-3. The model is available on HuggingFace, a platform that hosts language models and is often referred to as being open-weight: there is little documentation of the training data or process, but the model itself is openly available. While using a fully open model would be ideal, Llama-3 is highly efficient and produces outputs of high quality compared to other models that we tested. We used our own datasets to further fine-tune Llama-3; this means we used simplification data to adjust the model to perform better at this specific task. With the condition of sustainability in mind, we used efficient fine-tuning techniques that result in lower emissions. Finally, we performed an in-house evaluation, with annotations done by our team, so we could ensure fair working conditions.

Open validation and deliberation

We have made the thinking process behind Simba public knowledge, with articles such as this one and research papers in the pipeline. Additionally, our code is on GitHub, our models are accessible on HuggingFace, a subset of our training data is documented and publicly available and our website is accessible to the public. On our website, we have tried to adapt the information about Simba so that it can be understood by an audience that is technically less well versed. We began the project by consulting the existing literature, talking to experts and holding an initial consultation with potential stakeholders, that is, a group of researchers who have experience with disability and discrimination. We also explicitly ask for feedback and actively encourage other researchers, professionals and dedicated users from the simplification world to collaborate with us and help us make Simba better. So far, we have exchanged thoughts and ideas with a variety of organisations and potential users. We believe that it is only through collaboration that we can truly have a tool that works for as many different people as possible.

The openness of Simba – including explanations tailored to different target groups – meets a necessary prerequisite for participation and deliberation. However, we propose that requirements and expectations for projects – particularly in regards to participation – should be adapted depending on the scale of the project. Initiatives realised by public sector bodies, by mid to large commercial entities and by small non-profit groups will have different resources available and potentially have a different impact. For Simba, a more participatory design process would have been difficult, given the costs of involving stakeholders and users and the intricacies involved in design.

A strong foundation

Overall, our original thoughts on public interest AI provided a valuable foundation for thinking about AI for the public. And since we published these thoughts, we have learned from a variety of public interest AI projects, including our own prototypes. Our experiences with developing Simba have shown us that the principles we formulated at the beginning of the project are still relevant, but that slight adjustments would be valuable. In particular, having a justification, technical safeguards, being open for validation and fostering collaboration are important factors regardless of the size and scope of a project, whereas participation and sustainability should be considered in a more nuanced way. Simba, for example, has been developed in the context of a research project by a small team; including more participatory processes would be difficult given the costs of involving stakeholders/users and the intricacies involved in (co-)design. Additionally, as is the case for many research projects, success is often measured by academic publications and less so by practical output. Ideally, in the long term, more economic resources and incentives should be dedicated to practical outputs created in research contexts. In the meantime, we hope that this documentation of our insights and lessons learned will help researchers and developers navigate their own public interest AI projects.

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Artificial intelligence and society

The Human in the Loop in automated credit lending – Human expertise for greater fairness

How fair is automated credit lending? Where is human expertise essential?

Impactful by design: For digital entrepreneurs driven to create positive societal impact

How impact entrepreneurs can shape digital innovation to build technologies that create meaningful and lasting societal change.

Identifying bias, taking responsibility: Critical perspectives on AI and data quality in higher education

AI is changing higher education. This article explores the risks of bias and why we need a critical approach.