Making sense of our connected world

Small business manager or entrepreneur – who is more entrepreneurial?

In today’s fast-moving, connected world, it has never been more important to understand what determines the success or failure of a business. Particularly, small and medium businesses (SMB) and startups are regarded as a source of employment, growth and innovation in the German economy. For both types of businesses, the owners/founders are the central driving force behind their respective success or failure. The question arises first, how small business owners and entrepreneurs differ in their motivation, strategic focus and leadership. And second, how they can use their entrepreneurial skills in order to succeed in the light of technological change.

Generally, there are two ways to define an SMB (Schaper, 2011). First, employing quantitative metrics, the European Commission defines small and medium businesses as companies that employ less than 250 employees and have an annual turnover of fifty million EUR or less. Startups generally fit into this quantitative definition and can thus be viewed as a subgroup of SMBs.

Second, qualitative metrics provide additional insights into what makes SMBs such a particular group of businesses, and in particular, what distinguishes SMBs from startups. Most SMBs are owned by only one or two individuals, often over many generations within the same family. They typically combine ownership as well as managerial and financial control in one person. This person controls all key events and decisions within the business from its foundation to resource and investment allocations to strategic change. Their business strategy and operational focus often concentrate on a particular niche market or region. Although the innovation potential may thus be high, it rarely results in scalable growth as the market segments are too specific.

Startups, similar to SMBs, are owned by one or few individuals. However, they are often financed by venture capital and thus have a more complex ownership structure. Additionally, they are often younger than ten years and leverage technological innovation for their business model. The business strategy mostly focuses on scalable growth and changing the status quo in a particular customer segment or industry.

Small business managers are often regarded as entrepreneurs and vice versa (Schaper, 2011). However, the two differ significantly in their leadership style and motivation to run a business. Small business managers mostly run established SMBs, often over many generations, that focus on solving a problem in their community or a small niche market. They are focused on operational aspects and make calculated decisions when it comes to investments and resource allocation. Their main motivation for running the business is to maintain a sustainable business and employment situation (Volery et. al, 2015).

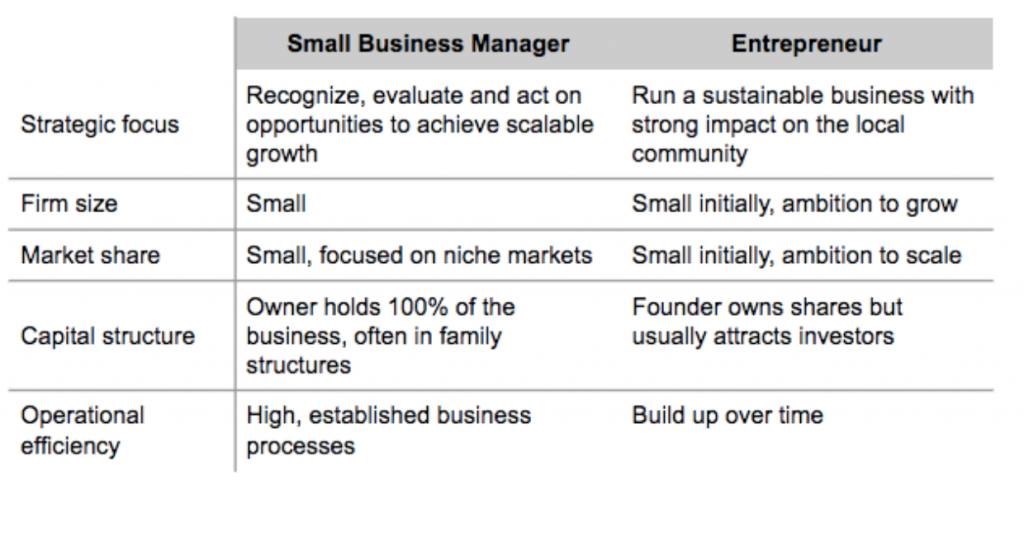

As opposed to entrepreneurs. Those agile managers perceive, evaluate, and act on opportunities within the environment. They usually intend to provide novel value propositions to a customer segment. Thus, they often create novel business models and expand into unknown markets without knowing if the idea will succeed or fail. Put differently, they are much more willing to make risky decisions under high uncertainty. While many entrepreneurs initially found a company that is characterized as a small business by quantitative metrics, their motivation and vision for the business is much more focused on scalable growth and continuous innovation. This may result in a transition to a larger firm eventually. Table 1 summarizes the differences.

Table 1: Differences between Small Business Managers and Entrepreneurs (based on Volery et al, 2015)

Notably, many differences exist between small business managers and entrepreneurs. However, one shall not be set above another. To the contrary, both small business managers and entrepreneurs are essential contributors to a well-functioning economy. Small business managers hold the economy, shape and impact their community, and provide a sustainable base of employment and income. Entrepreneurs facilitate growth and innovation. An important question arises though – how can both small business managers and entrepreneurs ensure that they maintain a successful business in today’s fast-moving, connected business environment?

A vital success factor for this are entrepreneurial skills, meaning the ability to recognize, evaluate and prioritize opportunities (Helfat & Peteraf, 2015) and subsequently the ability to act on those opportunities (George & Bock, 2011). Four (fictional) examples show how different types of managers and entrepreneurs can use their entrepreneurial skills to succeed in a fast-moving world.

Herbert, the Patriarch. He runs his established business in the 4th generation. His son recently joined the business to run its operations and will take over the entire business within the next five years. Herbert is proud of the business he build and the role it plays in its local community. He values the status quo and focuses his attention and efforts on identifying opportunities to optimize it. Thus, he has recently invested into a new production facility that streamlines the existing production processes. He is very well connected within his industry and a respected stakeholder for customers, partners and suppliers. The business has been recognized as a great place to work and has maintained a small but healthy growth over many years. His main motivation is to provide a sustainable income for both his family and his employees and ensure that the business will survive for the next generations to come.

Jochen, the Experimenter. He founded his own business while he was still in college and has grown it successfully since. He always looks for the next big thing and is always up-to-date on all the latest technological trends. He often recognizes opportunities that could change the way of the game substantially. While he enjoys prototyping products or services based on those opportunities, he is not willing to invest significant resources or capital into making them marketable. Still, he is often able to translate smaller aspects of his big ideas into optimizations for his current business processes. His employees value his strong innovative vision and thus live a very collaborative and open culture of innovation. His main motivation is exactly this – to run a well functioning business with a strong innovation culture. He hopes to hand over all management tasks to his daughter eventually.

Jochen, the Experimenter. He founded his own business while he was still in college and has grown it successfully since. He always looks for the next big thing and is always up-to-date on all the latest technological trends. He often recognizes opportunities that could change the way of the game substantially. While he enjoys prototyping products or services based on those opportunities, he is not willing to invest significant resources or capital into making them marketable. Still, he is often able to translate smaller aspects of his big ideas into optimizations for his current business processes. His employees value his strong innovative vision and thus live a very collaborative and open culture of innovation. His main motivation is exactly this – to run a well functioning business with a strong innovation culture. He hopes to hand over all management tasks to his daughter eventually.

Björn, the serial entrepreneur. He has founded several businesses over the last 10 years but none of them turned out to be profitable in the long run. His ideas are always big and he dreams of pushing the limits of existing business practices. This has led him into very different industries and customer segments, always jumping on new opportunities and trying to change the status quo. He does not shy away from risky investments into even the craziest business idea. However, he has struggled in the past to create a sustainable business model around his ideas. His main motivation is to change the game with his innovative ideas and achieve significant growth in a short period of time. His aim is not to run the same business for many years but rather to hand over the management as soon as the idea is marketable and move on to the next big thing.

Björn, the serial entrepreneur. He has founded several businesses over the last 10 years but none of them turned out to be profitable in the long run. His ideas are always big and he dreams of pushing the limits of existing business practices. This has led him into very different industries and customer segments, always jumping on new opportunities and trying to change the status quo. He does not shy away from risky investments into even the craziest business idea. However, he has struggled in the past to create a sustainable business model around his ideas. His main motivation is to change the game with his innovative ideas and achieve significant growth in a short period of time. His aim is not to run the same business for many years but rather to hand over the management as soon as the idea is marketable and move on to the next big thing.

Sven, the sustainable innovator. He just founded his second business, after selling his first business successfully to the biggest competitor. He was able to translate his first business idea into a well functioning value proposition for a big customer segment and corresponding resources and structures. The firm was known for its great working environment and collaborative culture. He made some risky decisions along the way, but always carefully evaluated the risks to ensure that his employees would have a secure job. His main motivation is to make a lasting impact in a certain industry and create an innovative business that may eventually evolve into a larger company with a significant market share.

Sven, the sustainable innovator. He just founded his second business, after selling his first business successfully to the biggest competitor. He was able to translate his first business idea into a well functioning value proposition for a big customer segment and corresponding resources and structures. The firm was known for its great working environment and collaborative culture. He made some risky decisions along the way, but always carefully evaluated the risks to ensure that his employees would have a secure job. His main motivation is to make a lasting impact in a certain industry and create an innovative business that may eventually evolve into a larger company with a significant market share.

References

- George, G., & Bock, A. J. (2011). The Business Model in Practice and its Implications for Entrepreneurship Research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(1), 83–111.

- Helfat, C., & Peteraf, M. (2015). Managerial cognitive capabilities and the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 36(6), 831–850.

- Schaper, M., Volery, T., Weber, P., Lewis, K. (2011). Entrepreneurship and small business.

3rd Asia Pacific Edition. Milton: John Wiley & Sons Australia. - Volery, T., & Mazzarol, T. (2015). The evolution of the small business and entrepreneurship

field: A bibliometric investigation of articles published in the International Small Business Journal. International Small Business Journal, 33(4), 374–396.

This post is part of a weekly series of articles by doctoral canditates of the Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society. It does not necessarily represent the view of the Institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and asssociated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

Photo: giphbay.com

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Digital future of the workplace

AI at the microphone: The voice of the future?

From synthesising voices and generating entire episodes, AI is transforming digital audio. Explore the opportunities and challenges of AI at the microphone.

Do Community Notes have a party preference?

This article explores whether Community Notes effectively combat disinformation or mirror political biases, analysing distribution and rating patterns.

How People Analytics can affect the perception of fairness in the workplace

People Analytics in the workplace can improve decisions but may also heighten feelings of unfairness, impacting employee trust and workplace relationships.