Making sense of our connected world

Skills to ‘race with the machines’: The value of complementarity

Artificial intelligence puts pressure on workers and firms. As workers are constantly urged to reskill, how can they determine which skills to invest in? We examine this question using data from one of the world’s largest online freelancing platforms. The results show the importance of complementarity. Skills rarely stand alone; their value depends on how well they complement other skills. Understanding and harnessing this complementarity is key to adapting to the changing work landscape.

The emerging need for workers with skills

Will we be racing against or with the machines (Brynjolfsson and McAfee 2012)? In today’s work landscape, the fate of both employees and businesses hinges on their ability to comprehend and adapt to technological shifts (Acemoglu 2021). Emerging technologies, like artificial intelligence (AI), have the potential to substitute human labour, yet they can also generate employment opportunities and growth if there is a demand for workers to operate these technologies or if novel economic activities surface (Ilzetzki and Jain 2023, Hötte et al. 2022).

As jobs that disappear differ in skill requirements from the newly created roles, workers face the risk of joblessness while companies struggle to find suitable employees for these new positions. To stay employed, workers must acquire new skills and blend them with their existing ones. Employers must invest in reskilling their workforce and talent acquisition. However, for many of these emerging jobs, the precise skill requirements remain unclear and are constantly evolving.

Keeping up with the labour market

Technological and social transformations are outpacing national training systems (Collins and Halverson 2018). The dilemma of which skills to prioritise in the era of digital transformation is particularly daunting for workers who have spent considerable time in the job market and lack the resources to rebuild their skill portfolio from scratch. They must seek synergy between their existing skill set and new capabilities. Consequently, policymakers, businesses, and workers are all in pursuit of skills that can secure their future in the workplace. But the central question remains: how can they determine which skills to invest in?

Complementarity: The key to a skill’s value

To address this question, we analysed a decade’s worth of skill profiles of around 25,000 knowledge workers from one of the world’s largest online freelancing platforms (Stephany and Teutloff 2024). We estimate the value of a skill as a premium that helps to increase worker wages in addition to other factors, such as occupation type or experience. Our central finding is that complementarity is the key to determining the value of a skill. Complementarity refers to how well a skill complements and enhances other skills. Here’s why it matters:

- Skill sets: Rarely do we apply a skill in isolation. Most jobs require a combination of skills. Therefore, the value of a skill can only be assessed in the context of its complementary skills.

- Reskilling efficiency: As workers adapt to new technologies, they incrementally add new skills to their existing skill sets. Maximising complementarity between old and new skills is crucial for economic efficiency in this process.

- Strategic value: As a particular skill’s set of complementary skills becomes more diverse, the more strategic options a worker has for reskilling. This increases their resilience against unforeseen technological changes in the future.

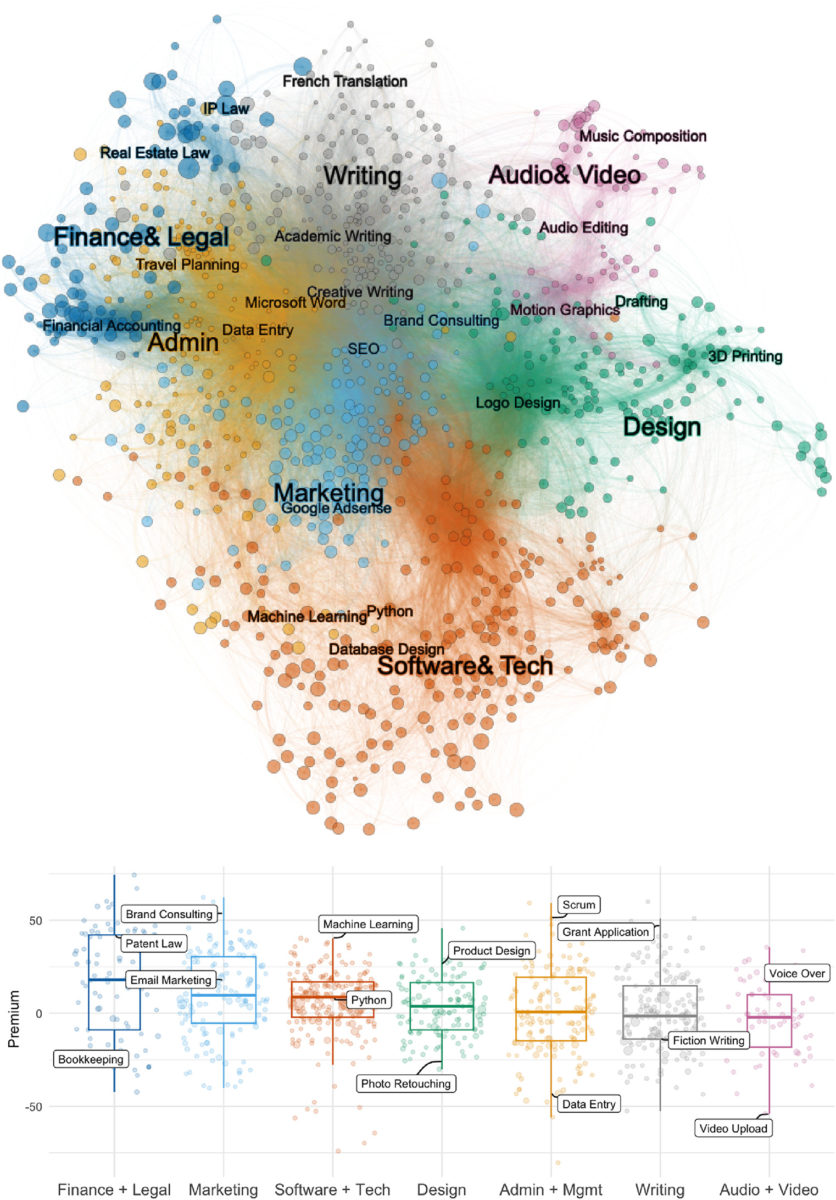

Figure 1 illustrates how skills are related in our dataset. In the upper panel of Figure 1 each node represents a skill. Two skills are connected if they have been applied jointly by a worker. The more closely two skills are related in this network, the more frequently they have been applied together. Based on this logic, we have identified seven groups of skills, which relate to different domains of skills in knowledge work: Finance and Legal, Marketing, Software and Tech, Design, Admin and Management, Writing, and Audio and Video. This first preliminary analysis reveals that skills of similar type (colour) and value (node size) cluster together. We further applied econometric modelling in our paper to investigate how the “neighbourhood” of adjacent competencies determines a skill’s value.

Our study demonstrates that the value of a skill is influenced by complementarity in three ways. First, options matter – a skill is more valuable if it can potentially be combined with numerous other skills. Second, the value of a skill depends on the variety of other skills it can be combined with. The more diverse the ‘neighbourhood’ of complements is, the more valuable a skill. Lastly, not only the number but also the value of complements affects a skill’s worth. A skill becomes more valuable if its complements are of high value as well. In addition to complementarity, skills become more valuable if they are in high demand relative to the available workforce.

AI skills: Our chance to ‘race with the machines’

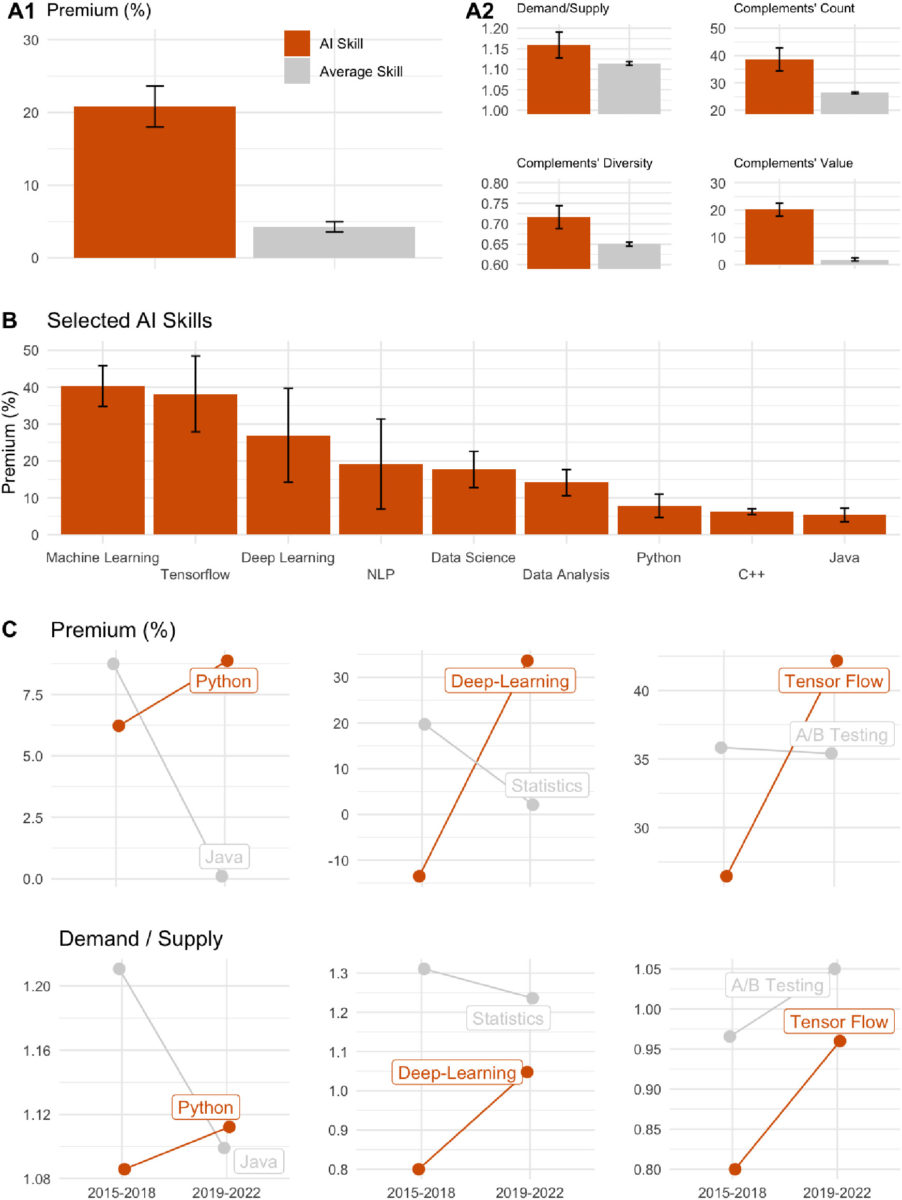

To put our concept into practice, we focus on the skills related to AI. AI is at the forefront of technological innovation, creating new opportunities and demands for specific skills. Indeed, in our model, AI skills, such as programming languages and data analytics, have proven to be particularly valuable – increasing worker wages by 21% on average, as shown in Figure 2. But why?

AI skills exhibit strong complementarity with various other skills, both in terms of number and diversity. In addition, the other skills that AI competencies are combined with tend to be of high value themselves (Figure 2, panel A2). This makes them highly adaptable and valuable in a variety of contexts. They have entered various fields of knowledge work, from graphic design to translation work to software development. In addition, the demand for AI skills has been on the rise in recent years (Figure 2, panel C). As industries across the board embrace AI, workers with AI skills are in high demand, leading to increased wages.

Reskilling: Empowering workers and firms

We believe that our findings have strong implications for individuals, businesses, and policymakers. By recognising the value of complementarity, we can better guide workers on their reskilling journeys. For organisations, investing in the development of AI skills among their workforce is an investment in the future. Some countries and employers are actively promoting the learning of digital skills through various initiatives. For instance, the Netherlands offers guidance and grants for training to workers over 45 in the ICT sectors. Sweden, through the Digidel network, provides digital skills training for older adults. In the US and the UK, companies like Verizon and Citi are offering apprenticeships and in-house training for data and digital skills development.

In conclusion, the world of work is evolving, and adaptability is the key to success. Understanding the complementarity of skills is essential in making informed decisions about where to invest in your skill development: Learning the same skill might pay differently, depending on which skills you already have. Our research supports the European Commission’s policy recommendations that advocate for personalised learning strategies – ideally carried out within firms – and more flexible certification options for competencies acquired through vocational training, short courses, or training programs. These flexible certifications, often referred to as ‘micro-credentials’, are in high demand to ensure that both workers and employers are well-equipped to navigate the ever-evolving landscape of the future of work.

Authors

Fabian Stephany is an associated researcher at the Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society within the Innovation, Entrepreneurship & Society research group. Fabian is also working as an economist and social data scientist at the Oxford Internet Institute (OII), University of Oxford.

Ole Teutloff is a PHD Fellow at the Copenhagen Centre of Social Data Science. He investigates the impact of digital technologies on society. In particular, I focus on the future of work.

References

Acemoglu, D (2021), “Dangers of unregulated artificial intelligence”, VoxEU.org, 23 November.

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (2009, March). Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. In Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media (Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 361-362).

Collins, A and R Halverson (2018), Rethinking education in the age of technology: The digital revolution and schooling in America, Teachers College Press.

Hötte, K, M Somers and A Theodorakopoulos (2022), “The fear of technology-driven unemployment and its empirical base”, VoxEU.org, 10 June.

Ilzetzki, E and S Jain (2023), “The impact of artificial intelligence on growth and employment”, VoxEU.org, 20 June.

Stephany, F and O Teutloff (2024), “What is the price of a skill? The value of complementarity”, Research Policy 53(1).

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Digital future of the workplace

AI at the microphone: The voice of the future?

From synthesising voices and generating entire episodes, AI is transforming digital audio. Explore the opportunities and challenges of AI at the microphone.

Do Community Notes have a party preference?

This article explores whether Community Notes effectively combat disinformation or mirror political biases, analysing distribution and rating patterns.

How People Analytics can affect the perception of fairness in the workplace

People Analytics in the workplace can improve decisions but may also heighten feelings of unfairness, impacting employee trust and workplace relationships.