Making sense of our connected world

AI in the hype cycle – A brief history of AI

In its eventful history, dating back to the 1950s, the research field of artificial intelligence (AI) has experienced several ups and downs. Sometimes the technology went through a phase of hype and governments invested enormous sums of public funding in the development and research of these technologies. Sometimes the interest of the public and politics in the topic decreased and funding was withheld from AI research. An essential role behind these ups and downs was often played by exaggerated expectations, which eventually ended in disappointment.

In 1973 the British AI research community was shocked. A report commissioned by the British Parliament confirmed that the field of research had achieved virtually none of its objectives in recent years. As a result, AI research projects were ceased and funds cut. Not only in Europe, but also in the USA, public funding of civil AI research almost came to a standstill. The US Congress passed a law restricting the funding of basic research without a direct military connection.

The seasons of AI

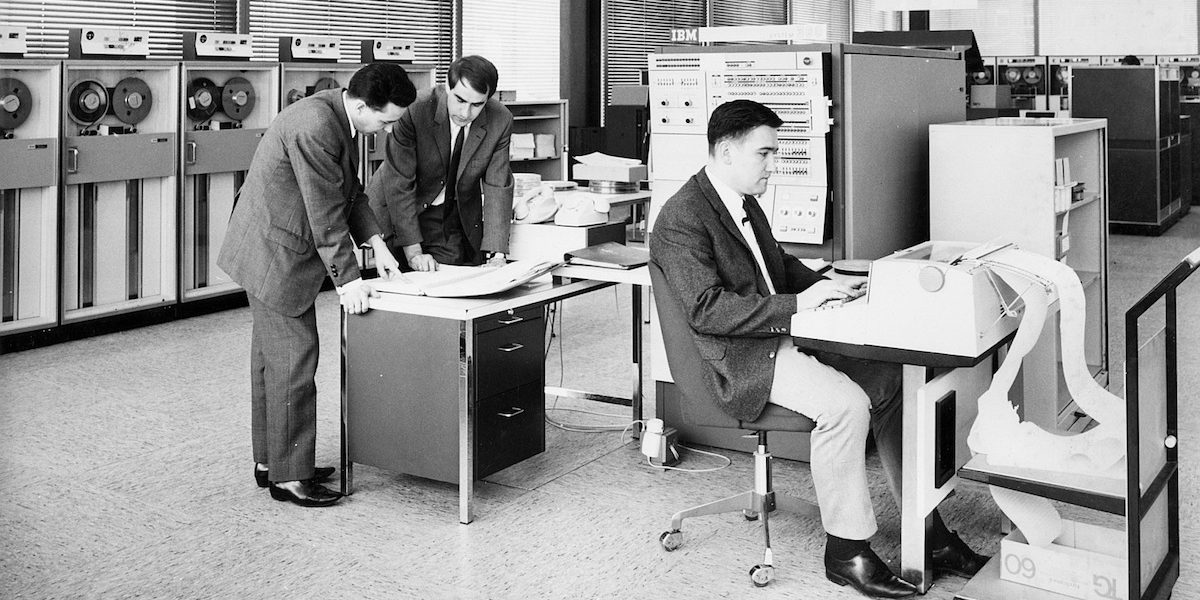

The events in the early 70s are today referred to as the first AI winter. The term describes an evident cooling of interest and research funding in the field of AI and was first coinedin 1984 at a conference of the American Association of Artificial Intelligence. The first AI winter was preceded by an unprecedented blossoming of the still utopian-looking technology that had formed at a science conference in Dartmouth in 1956. Scientists from the fields of mathematics, neuroscience and engineering designed the target image of an artificial intelligence that based on computer technologies, would be in no way inferior to human intelligence. Future visions of the first generation of AI scientists testify to the extreme optimism of the time. Herbert Simon, one of the early pioneers of AI, was enraptured by the statement in 1965 that AI would be able to fulfill all human tasks within the next 20 years.

Such optimistic assessments were one of the reasons why research funds flowed abundantly during this time. In addition, governments expected scientific advantages and technological superiority during the Cold War. When these hopes were not fulfilled, the first AI winter occurred, which would last until 1980. However, the research field quickly recovered. So-called expert systems gained popularity among scientists and public funding bodies in the early 1980s, and a whole new industry emerged. Like human experts, these computer programs were supposed to analyse data based on previously defined rules and tried to implement automatic decision making. However, they often failed in complex tasks and practical applications, as expert systems could not react to unexpected scenarios. Because humans had to dictate rules to the system, it required a lot of manual effort that did not justify the modest success. Accordingly, this hype phase, which persisted from 1980 to 1987, did not last. In the USA, funds for the Strategic Computing Initiative, which had financed AI research, and in Japan research budgets were cut. It was not until the mid-1990s that a new AI spring dawned. AI research was able to achieve some of the goals it had set thanks to more powerful hardware and extended data bases, and the topic was also met with an increased interest from the public. For example, the success of the chess computer, which beat the reigning world chess champion Garri Kasparov in 1997, brought new renown and attention to AI research.

AI in the hype cycle

These popularity cycles can best be described by hype cycles, a concept which was developed by the management consultancy firm Gartner. According to this concept, a new technology experiences several phases of attention. Initially, expectations are enthusiastic and often exaggerated, but they soon end in a “valley of disappointments”. After this phase – according to the concept of hype cycles – a technology enters a productive phase in which results are achieved beyond the attention of politics and the public.

This is likely the case with the ups and downs of AI technologies. Certainly, technological hurdles also played a role in the cyclical development of AI – for example, many applications were simply not possible in the past due to low computing capacities. But above all, unkept promises seem to have triggered the AI winters. But how could the AI winters be overcome and phases of real progress be initiated? It is reasonable to assume that a new terminology gave this field of research a more profound and realistic image. Whereas a general human-like intelligence had previously been promised, less high-sounding terms such as algorithmic decision systems, automatic speech recognition and artificial neural networks produced a more accurate picture of what is technically possible. This also reduced the danger of raising unsustainable expectations. Swedish technology philosopher Nick Bostrom describes the phenomenon as follows: “A lot of cutting-edge AI has filtered into general applications, often without being called AI because once something becomes useful enough and common enough it’s not labelled AI anymore.”

AI research today

At the moment, AI is experiencing another hype phase, which has even led to a race for AI in which states try to outbid each other with strategies and funding programmes. AI is regarded by politicians and investors worldwide as the central key technology of the future. In its “National AI Strategy“, for example, the German Federal Government calls for “Germany and Europe to become a leading location for the development and application of AI technologies” and intends to invest billions in the research and development of such technologies. AI obviously serves the leading technological powers as means or at least as a metaphor to demonstrate technological, but often also – in the form of lethal autonomous weapon systems – military power.

At the same time, it is unclear to what extent the political ambitions are bearing real fruit. A recent study showed that four out of ten European start-ups labelled AI do not use any AI technologies based on the analysis of large amounts of data. So, are expectations produced again in the current hype that cannot be met? It is quite possible that in the current cycle – to remain in the language of the seasons – we are already in late summer and a new AI winter is threatening. But an end to the hype would offer the chance to return to a more differentiated debate. In the early years of AI, researchers developed a vision of the future of a so-called “strong” AI that could think and act independently. In fact, however, “weak” AI technologies developed in the form of specialized individual solutions in limited sub-areas. Although AI was able to beat the chess world champion, the technology is still far from being able to think like a human being. A clear naming of the concrete AI technologies could take the extremes off the topic and also prevent horror scenarios. Many people associate AI with gloomy visions of highly intelligent computers that strive for human existence, such as those awakened in science fiction films. But we are still a long way from a superintelligence like the computer HAL 9000 from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: Odyssey in Space. Although there are few serious scientists who consider such visions to be realistic, visions and dystopias shape the social understanding of AI. A new AI winter could therefore be an opportunity to bring the debate back down to earth.

Header: © SLUB / Deutsche Fotothek / GERMIN

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Research issues in focus

Inside content moderation: Humans, machines and invisible work

Content moderation combines human labour and algorithmic systems, exposing global inequalities in who controls what we see online.

Beyond Big Tech: National strategies for platform alternatives

China, Russia and India are building national platform alternatives to reduce their dependence on Big Tech. What can Europe learn from their strategies?

Counting without accountability? An analysis of the DSA’s transparency reports

Are the DSA's transparency reports really holding platforms accountable? A critical analyses of reports from major platforms reveals gaps and raises doubts.