Making sense of our connected world

The balance between product development, growth and employee motivation in startups

Employee satisfaction and engagement are widely acknowledged as primary drivers of a firm’s productivity and innovativeness. This is particularly true for startups – a young, fast growing and innovative breed of firms that face a great deal of uncertainty. Startups typically do not have the resources to pay their employees competitive wages and to provide long-term employment security. Despite the significant economic loss that firms incur due to emotionally disengaged employees, founders and CEOs of startups still prioritize product development and short-term profitability over internal strategies geared towards harnessing a company’s most important asset: Its employees. This strategic discrepancy has to change, if startups want to grow into functioning, resistant companies that survive in the long run.

Mitarbeiter als wesentlicher Erfolgsfaktor für Unternehmen

Mitarbeiter und ihre Zufriedenheit beeinflussen die Produktivität und Innovationsfähigkeit eines Unternehmens maßgeblich (vgl. Judge et al. 2001; Wright/Bonett 2007; Page/Vella-Brodrick 2009). Somit besteht für Gründer und Geschäftsführer eine große Herausforderung darin, Rahmenbedingungen zu schaffen, die Mitarbeiter motivieren, fördern und langfristig an ein Unternehmen binden. Durch die üblicherweise geringere Entlohnung im Vergleich zu etablierten Unternehmen und die erhöhte Arbeitsplatzunsicherheit ist diese Herausforderung für Jungunternehmen besonders ausgeprägt.

Fehlende Mitarbeitermotivation und ihr volkswirtschaftlicher Schaden

Im internationalen Vergleich weisen deutsche Arbeitnehmer eine besonders geringe – und zunehmend sinkende – Arbeitszufriedenheit auf (vgl. Bohulskyy et al. (2011). Laut der jährlichen Studie des Markt- und Meinungsforschungsinstituts GALLUP (Engagement Index Deutschland) haben lediglich 15 Prozent der Beschäftigten in Deutschland eine hohe emotionale Bindung an Ihren Arbeitsplatz. 70 Prozent machen „Dienst nach Vorschrift“ und weisen nur eine geringe emotionale Bindung auf. Die übrigen 15 Prozent der Mitarbeiter haben bereits innerlich gekündigt. Der volkswirtschaftliche Schaden dafür beläuft sich nach Hochrechnungen von Nink (2015) auf bis zu 95 Mrd. EUR. Ursachen dafür sind u.a. Kosten für hohe Fluktuationsraten, negative Gesundheitseffekte bei den Mitarbeitern und schlechte Arbeitsergebnisse (vgl. Böckermann/Ilmakunnas (2009); Fischer/Sousa-Poza (2006).

Startups als besondere Form von Jungunternehmen

Startups, die durch die folgenden drei Merkmale definiert sind (Ripsas/Tröger 2015, S. 12):

- Startups sind jünger als 10 Jahre.

- Startups sind mit ihrer Technologie und/oder ihrem Geschäftsmodell (hoch) innovativ.

- Startups haben (streben) ein signifikantes Mitarbeiter und/oder Umsatzwachstum anstreben (an).

stellen eine besondere Form von Jungunternehmen dar, unterscheiden sich wesentlich vom allgemeinen Gründungsgeschehen (bspw. durch die Teamgröße, Innovationskraft, Anzahl der Mitarbeiter, Quelle und Höhe der Finanzierungen; (vgl. Ripas/Tröger 2015, S.11f.; 2014) und gelten nicht zuletzt als Jobmotoren – im Durchschnitt beschäftigen sie 15,2 Mitarbeiter (ohne die Gründer selbst; vgl. Ripsas/Tröger 2015, S. 35ff.).

Startup Strategien und die fehlende Fokussierung auf innerbetriebliche Strategien

Aufbauend zu den o.g. Ergebnissen zur Mitarbeitermotivation, deren Einfluss auf den Unternehmenserfolg, wurde die These aufgestellt, dass es, zumindest verglichen mit anderen Strategien, eine starke Fokussierung von Gründern auf die innerbetrieblichen Themen: Mitarbeitermotivation, Unternehmenskultur und Organisationsentwicklung geben sollte.

Daher wurde in Ergänzung zum Deutschen Startup Monitor 2015 (bis heute unveröffentlichtes Datenmaterial) der Frage nachgegangen:

„Welche Unternehmensstrategien sind für dein Startup aktuell wichtig?“

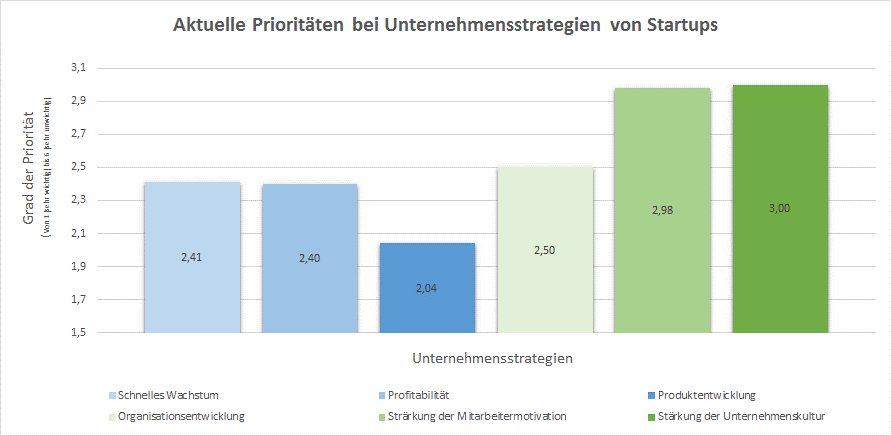

Im Ergebnis stellt sich heraus, dass die Produktentwicklung mit einem Mittelwert () von 2,04 aktuell die höchste Strategiepriorität vorweist, gefolgt von der Profitabilität (= 2,40) und schnellem Wachstum (= 2,41). Die im Vergleich niedrigsten strategischen Prioritäten, die jedoch wie o.g. die Treiber für Produktivität- und Innovationsgeschwindigkeit sind, weisen die innerbetrieblichen Themen: Organisationsentwicklung (= 2,5), Stärkung der Mitarbeitermotivation & Förderung (= 2,98) sowie die Stärkung der Unternehmenskultur (= 3,00) auf (siehe Abb. 1).

Abb. 1: Aktuelle Prioritäten von Strategien bei Startups (2015)

Eigene Darstellung; Frage: Welche Unternehmensstrategien sind für dein Startup aktuell wichtig?

Zusammenfassend ist festzustellen, dass sich nicht nur die Wissenschaft zu wenig mit dem Phänomen der innerbetrieblichen Unternehmensentwicklung und Professionalisierung von Startups auseinandersetzt (dazu u.a. Saßmannshausen/Volksmann 2012, S. 169; Fischer/Reuber 2003, S. 348), sondern dass auch Gründer und Geschäftsführer von Startups möglicherweise das Potenzial, welches eine stärkere Fokussierung der Themen Organisationsentwicklung, Mitarbeitermotivation und Förderung, sowie Stärkung der Unternehmenskultur, mit sich bringen könnten, verkennen.

Weitere Ergebnisse zur jährlich durchgeführten Startup-Studie gibt es hier.

This post is part of a weekly series of articles by doctoral canditates of the Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society. It does not necessarily represent the view of the Institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and asssociated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

Quellen:

- Böckmann, P. / Ilmakunnas, P. (2009): Job Disamenities, Job Satisfactions, Quit Intentions, an Actual Separations: Putting the Pieces Together, Abrufbar unter: http://www.petribockerman.fi/ bockerman%26ilmakunnas_job_2009.pdf, Zuletzt abgerufen am: 01.04.2014.

- Bohulskyy, Y./ Erlinghagen, M- / Schneller, F. (2011): IAQ-Report: Arbeitszufriedenheit in Deutschland sinkt langfristig, Institut Arbeit und Qualifikation, Abrufbar unter: http://www.iaq.uni-due.de/iaq-report/2011/report2011-03.pdf, Zuletzt abgerufen am: 01.04.2014.

- Fischer, J. A. V. / Sousa-Poza, A. (2006): Does Job Satisfaction Improve Health? New Evidence using Panel Data and Objective Measures of Health, Forschungsinstitut für Arbeit und Arbeitsrecht, Universität St. Gallen, Diskussionspapiere, Nr. 110.

- Fischer, E. / Reuber, A. R. (2003): Support for Rapid-Growth firms: A Comparison oft he Views of Founders, Government Policymakers, and Private Sector Resource Providers, Journal of Small Business Management 2003 41(4), S. 346-365.

- Judge, T. A. / Thoresen, C. J. / Bono, J. E. / Patton, K. G. (2001): The Job Satisfaction – Job Performance Relationship: a Qualitative and Quantitative Review, Psychologgical Bulletin 127, Nr. 3. S.376-407. Abrufbar unter: http://fagbokforlaget.no/boker/downloadpsykorg/KAP8/artikler/ Jobbtilfredshet.pdf, Zuletzt abgerufen am: 01.04.2014.

- Nink, M. (2015): Engagement Index Deutschland 2014, Gallup, Abrufbar unter: http://www.gallup.com/de-de/181871/engagement-index-deutschland.aspx, Zuletzt abgerufen am: 01.05.2015

- Page, K. M. / Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2009): The What, Why and How of Employee Well Being: A new Model, In Social Indicators Research, Nr. 90, S. 441-458.

- Ripsas, S. / Tröger S. (2014): Deutscher Startup Monitor 2014, KPMG in Deutschland, Berlin.

- Ripsas, S. / Tröger S. (2015): Deutscher Startup Monitor 2015, KPMG in Deutschland, Berlin.

- Saßmannshausen, S. P. / Volkmann, C. (2012): „Gazellen“- schnell wachsende Jungunternehmen: Definitionen, Forschungsrichtungen und Implikationen, ZfKE 60. Jahrgang, Heft 2 (2012), S. 163-177, Duncker & Humbolt, Berlin.

- Wright, T. A. / Bonett, D. G. (2007): Job Satisfaction and Psychological Well Being as Nonadditive Predictors of Workplace Turnover, in: Journal of Management, Nr. 33, S. 141-160.

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Digital future of the workplace

The Human in the Loop in automated credit lending – Human expertise for greater fairness

How fair is automated credit lending? Where is human expertise essential?

Impactful by design: For digital entrepreneurs driven to create positive societal impact

How impact entrepreneurs can shape digital innovation to build technologies that create meaningful and lasting societal change.

Identifying bias, taking responsibility: Critical perspectives on AI and data quality in higher education

AI is changing higher education. This article explores the risks of bias and why we need a critical approach.