Making sense of our connected world

Hate speech and fake news – how two concepts got intertwined and politicised

On 1 October 2017, the so-called Network Enforcement Act (Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz, or NetzDG) came into force with a transitional regulation. The law applies to operators of social media platforms and their handling of the phenomena of hate speech and fake news. As the jury for the Anglicism of the Year 2016 award wrote, these two terms served as a “crystallisation point for societal debates on how to deal with this phenomenon, which is not entirely new but has entered the public consciousness with force.” We ask: how did it come about that the debates around these terms actually led to a law in Germany?

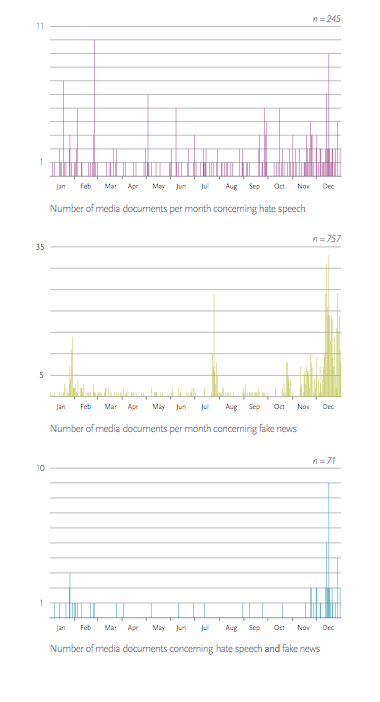

To answer this question, we will first reconstruct the trajectories of the two discussions in the media. The debates on hate speech and fake news are first considered separately from each other; then, we examine how they came into contact with one another. We will subsequently turn our attention to the increasing politicisation of the discussions, which culminated at the end of the year in a convoluted discourse on the regulation of two very different phenomena. Our accounts here are based on an analysis of more than 900 articles published in the German-language media in 2016.

TRAJECTORY OF THE HATE SPEECH DISCUSSION IN 2016

At the beginning of 2016, Facebook itself shaped the media agenda by announcing several measures to combat hate speech, with a focus on Germany. At the end of May, the question of how to deal with hate speech also became an issue for European institutions. The European Commission reached an agreement with Facebook, Google, Microsoft and Twitter on a code of conduct on hate comments. In Germany, a local case of right-wing agitation against Green Party MEP Stefanie von Berg once again put the topic on the media agenda. Hamburg’s senator of justice, Till Steffen (Green Party), then pushed the discussion about a possible tightening of the law on hate crimes. Over the summer of 2016, the media interest was fuelled by a larger discussion broadening the scope of the issues to society as a whole. In these months, various actors initiated public campaigns against hate speech, and projects to observe hate speech on the internet were set in motion. The first figures and statistics based on scientific research were published. The wider public interest strengthened the drive to political action.

The enormous increase in reporting in November and December was primarily the result of the superimposition of another discourse onto this debate. The US presidential election and the question of how fake news on social media had influenced it reactivated the debate on online hate comments at the end of 2016 as just another category of unwanted content on the internet. As an overview, the following graph shows the trends on the hate speech discussion in 2016.

TRAJECTORY OF THE FAKE NEWS DISCUSSION IN 2016

At the beginning of 2016, reports of defamatory, false stories about refugees increased. Our analysis shows, however, that these false reports were not yet the focus of a separate discourse; instead, the lines of conflict were based more on positions in the refugee debate.

We again note an increased focus on false reports during the shooting spree in Munich on 22 July 2016. The term Falschmeldung (literally false report) used in this context primarily referred to rumours that were spread as purported facts during the chaos. Nevertheless, the killing spree in Munich marked an important point in the development of the fake news discussion in several respects. It was here that key subjects and objects of discourse formed: on the one hand, there was social media platforms, which is where false reports were primarily spread. On the other hand, there were traditional media organisations, which were accused of allowing an information vacuum to emerge, thus giving the false reports on Twitter or Facebook more opportunity to spread. Calls for state intervention were voiced for the first time with reference to the coverage of the killing spree, but considerations remained abstract.

The issue finally came to the public’s attention along with the entry of the English term fake news into the German language – this occurred when Facebook was accused of aiding President Trump’s election victory. While the debate had previously centred on concrete cases of false reports and problematised their dissemination, now Facebook’s handling (or non-handling) of fake news was the subject of discussion. There were calls for measures that would go beyond a mere voluntary commitment on the part of Facebook. In December, the problem was then also applied to the forthcoming federal elections in Germany in 2017. As the second visualisation on page 67 shows, this resulted in yet another rise in reporting.

CONVERGENCE OF TWO DISCUSSIONS INTO ONE DISCOURSE

At the beginning of 2016, both phenomena arose simultaneously but individually in certain contexts: for example, there were increasing numbers of false reports against refugees that were deliberately being spread to incite hatred. However, in terms of terminology, the term that was being used was exclusively false reports with defamatory content (Falschmeldungen mit diffamierenden Inhalten).

By the end of the year, two Anglicisms had established themselves in the German language: hate speech and fake news. In this phase, the hate speech discussion almost never appears in isolation. The intermingling of the two discussions is particularly apparent in December. Of the 49 articles on hate speech published in December, 37 articles also deal with fake news. The hate speech discussion was increasingly subsumed under the new fake news debate.

At the end of 2016, the factor that connected these two, previously separate discussions was not that they occurred simultaneously in relation to certain incidents, but that both phenomena arose in the same place. Social media platforms, especially Facebook, were seen as the breeding ground for fake news and hate speech and were increasingly criticised. Two distinct categories of unwanted content had now become the subject of the same regulatory efforts. The third visualisation on page 67 depicts the convergence of the discussions in 2016.

POLITICISATION OF THE DISCUSSION: A WAY STATION ON THE PATH TO THE LAW

The above explanations mark the way stations on the path to the Network Enforcement Act: platforms launched initiatives and made voluntary commitments regarding hate comments in early 2016, there was a broader societal discussion of the topic during the summer months, an increased focus on the role of digital platforms in spreading hate comments and false reports, and finally the election victory of Trump, which firmly anchored the English terms fake news and hate speech in the German discourse and united the two debates in their criticism of Facebook’s deletion practice.

The politicisation of these two discussions was fuelled in particular by three factors. First, politicians (e.g. Renate Künast, Stefanie von Berg) were themselves victims of false statements or hate tirades in social networks. Second, the initial measures in the fight against hate speech, which were mainly based on platforms’ own initiatives and voluntary commitment, were increasingly perceived as ineffective. And third and finally, the discourse about hate speech and fake news on social media platforms was situated in a relationship with other political issues, in particular the refugees, the killing spree in Munich, alleged disinformation campaigns by foreign governments, and finally, the federal parliamentary elections in Germany following the US elections.

These factors prompted a shift in the debate towards legislative solutions. At the same time, the emerging narrative of fake news as a threat to German democracy in the face of the forthcoming elections led to an increased sense of urgency within politics. In this context, the new fake news problem was quickly linked to the old hate speech issue. A longer discussion, of the kind that emerged on hate speech, in which participants first attempted to better understand, define and evaluate the problem, did not happen in the case of fake news. Because voluntary measures taken by platform operators against hate speech had purportedly led to disappointing results, politicians now sought to solve the fake news problem by directly legislating.

WHAT WILL REMAIN THE SAME, WHAT WILL CHANGE?

In the spring of 2017, these developments culminated in a draft law presented by then Justice Minister Heiko Maas. In June of the same year, despite harsh criticism, the draft was accepted by the Bundestag and finally implemented on 1 October 2017 – albeit in watered-down form. Supporters and critics of the law see the actual problem quite differently: while proponents see hate speech and fake news as a threat to German democracy and the law as a way of defending against this, critics see the law itself as a threat to democratic opinion-formation. These critics fear that platforms may proactively delete content on a large scale to avoid fines. In addition, they are concerned that the law could be abused by governments. In both cases, there would be a threat of censorship and thus a restriction of freedom of expression. While our analysis is limited to the year 2016, based on these contradictory positions, we can predict that the NetzDG, its controversial norms and legality, and the concrete effects of the law will continue to be a subject for debate.

REFERENCES

Anglizismus des Jahres. (2016). Retrieved from http://www.anglizismusdesjahres.de/anglizismen-des- jahres/adj-2016

Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz vom 1. September 2017 (BGBl. I S. 3352) (Germany). Retrieved from https:// www.gesetze-im-internet.de/netzdg/BJNR335210017.html

This piece is based on two articles published on 2 and 8 May 2017 on the Science Blog of Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society (HIIG).

Kirsten Gollatz is currently conducting research with a focus on the conditions for exercising freedom of expression on the internet and the relevance of private transnational governance, as well as online participation. Along this line, Kirsten is interested in how public discourses, for instance on hate speech and fake news on digital platforms in Germany, manifests itself in institutions, new organisational processes or practices. Kirsten Gollatz is Project Manager at HIIG working at the interface between the institute’s research agenda and a growing international research community. Kirsten also coordinates the institute’s academic visitor programs. Since 2014 Kirsten has been writing her doctoral thesis at the University of Zurich. In her thesis she investigates the evolution of transnational governance regimes that private social media companies apply to user content on their platforms.

Leontine Jenner is a student assistant for the Internet Policy and Governance research team at HIIG. She is currently studying sociology at the Technical University of Berlin with an emphasis on sociological technology studies and computer science as her minor field. Prior to her studies she has worked in the games industry in the field of game design. Leontine is particularly interested in new forms of digitally mediated interaction and qualitative and digital research methods.

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Research issues in focus

Polished yet impersonal: The unintended consequences of writing your emails with AI

AI-written emails can save workers time and improve clarity – but are we losing connection, nuance, and communication skills in the process?

AI at the microphone: The voice of the future?

From synthesising voices and generating entire episodes, AI is transforming digital audio. Explore the opportunities and challenges of AI at the microphone.

Do Community Notes have a party preference?

This article explores whether Community Notes effectively combat disinformation or mirror political biases, analysing distribution and rating patterns.