Making sense of our connected world

How “Leave” won Twitter: an analysis of 7.5m Brexit-related tweets

How did Eurosceptic (leave) and pro-European (remain) activity compare on social media in the run-up to the EU referendum, and was there a relationship between social media users and votes? To find out how leave and remain compared, we collected more than 7.5 million Brexit related tweets during the 23 days leading up to the referendum through Twitter’s streaming API. We used a support vector machine to identify which tweets clearly supported the leave or remain camp (and manually coded a random sub-sample of those tweets to ensure our allocation was reliable). Due to the polarizing nature of the issue, the process worked well, and the model correctly identified most tweets. We used the result of this exercise to assign each user in our sample to one of the two camps.

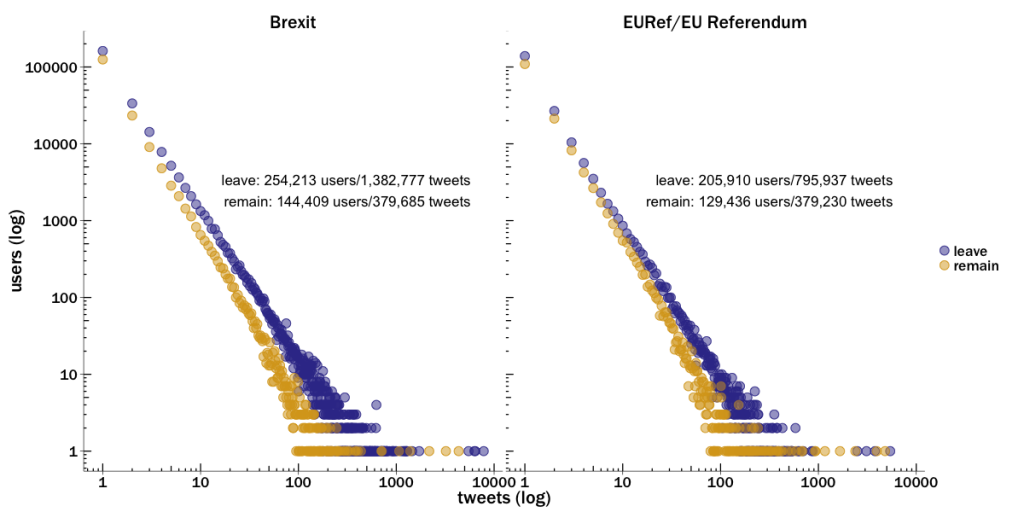

We collected tweets containing the terms Brexit, EUref and EU Referendum, all of which were frequently used to refer to the referendum. While the term Brexit has great currency across both camps, it was used more often by users who wanted to leave the EU as it lends itself more easily to positive slogans, e.g. “Can’t wait for #Brexit to win!” or “Brexit to save Europe” and “Brexit means Brexit”. Even though EURef and EU Referendum are more neutral terms, in both sub-samples we found that support for leaving, measured by the number of tweets, outstripped support for remaining by a factor of 2.3 and 1.75 respectively. The margins confirm a slight bias in the term Brexit, where the strength of leave over remain was more pronounced. Overall it is clear that the army of leave users was larger in number and more active in tweeting their cause (see Figure 1).

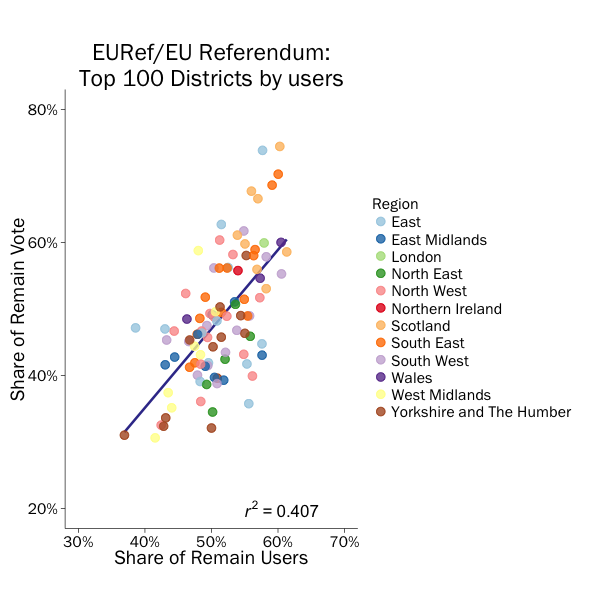

Other researchers examining Google search trends, Instagram posts, and Facebook found something similar – i.e. that Eurosceptic views were being communicated with greater intensity by a greater number of users. Researchers from Loughborough University revealed that, weighted for circulation, 82% of newspaper articles were pro-Leave (Loughborough University, 2016). British people had greater exposure to Eurosceptic than pro-European opinions in both print and social media. We also mapped Twitter activity onto local authority districts. To do this, we used Google’s and Bing’s geo coding services to translate user-provided location information into geographical coordinates, which we then matched with local authority districts. This is not an exact science, both because many users provide no or fictitious location information in their profiles, and because the more granular the geo-location information required, the more error-prone the result. As many users specify their location as London rather than its constituent boroughs, we aggregated all tweets from users located there. We plotted the share of users supporting remain against share of the remain vote. We excluded districts where we identified fewer than 200 users, giving us usable data for 100 local authorities.

There is clearly a pattern in how the referendum campaign unfolded on Twitter, with those wanting to leave communicating in greater numbers and with a greater intensity. Districts with a greater share of Twitter users supporting leave also tended to vote for leaving the EU, meaning that Twitter activity correlates with voting in the referendum. Yet we must be cautious to avoid over-interpretation. This particularly applies to claims that social media can predict election outcomes, the problems of which have been pointedly enumerated. Finding a pattern in the data post hoc is quite a different thing than confidently identifying and interpreting the pattern ex ante – the leave camp was ahead on social media by a much larger margin than it ultimately was in the vote. This means it is unclear how researchers could have interpreted the results of a Twitter analysis before the vote. The most significant problem is that we lack the demographic descriptors of social media users that would enable us to weight or interpret results.

Nevertheless, given that Twitter users are generally thought to be younger and young people tended to vote remain, the result is surprising either way. It seems plausible that leave voters were more motivated, and consequently more active on Twitter. It also seems likely that slogans such as vote leave, take control, or even Brexit lent themselves better to a simple message (this is particularly useful given the constraints of a tweet), and allowed different interpretations, with the result that users could project their desired meaning onto the slogan. Whether in the press or on social media, British voters were more likely to encounter messages that favoured leaving the EU than those that favoured remaining.

This blogpost was first published on the Brexit blog by London School of Economics. Stefan Bauchowitz holds a PhD from the London School of Economics. Max Hänska is a lecturer (Assistant Prof.) at De Montfort University (UK) where his research interests center on social media, political communication and collective decision-making. During the summer he was a visiting researcher at HIIG.

References

Loughborough University (2016). 82% circulation advantage in favour of Brexit as The Sun declares.

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Research issues in focus

Emotionless competition at work: When trust in Artificial Intelligence falters

Emotionless competition with AI harms workplace trust. When employees feel outperformed by machines, confidence in their skills and the technology declines.

Defending Europe’s disinformation researchers

Disinformation researchers in Europe face lawsuits, harassment & smear campaigns. What is behind these attacks? How should the EU respond?

Debunking assumptions about disinformation: Rethinking what we think we know

Exploring definitions, algorithmic amplification, and detection, this article challenges assumptions about disinformation and calls for stronger research evidence.