Making sense of our connected world

Lowering the barriers: Accessible language and “Leichte Sprache” on the German Web

The inventor of the web, Tim Berners-Lee, stated that “the power of the Web is in its universality. Access by everyone, regardless of disability is an essential aspect”. This statement, from the 1990s, rings even more true in 2023, as participation in society depends on being able to access the web for information, services, and connections. In this blog post, we will outline our findings on the question: how much German-language web content is also available in Leichte Sprache?

Easy-to-read

Leichte Sprache (LS), literally translated to English as Easy Language, is a set of formal rules which a text should adhere to if it is to be understood by its target group: people with cognitive disabilities. This German branch of easy-to-read language has been around since the early 2000s, but has gained more traction in recent years due to various legal requirements.

It’s a Ländersache

One of these legal requirements is the Web Accessibility Directive, enacted by the EU in 2016. It requires public sector websites to be accessible to persons with disabilities. The Directive describes four principles for accessibility, one of which is ‘understandability’. While most EU countries transposed the Directive in one or two laws, Germany has created 54 national laws based on the Directive. And this is where the easy language situation starts to get complicated: Around two thirds of German states have accessibility laws which require their state and municipal websites to provide the gist of the website’s content in LS. But in six states the law refers to a different standard and bypasses the rules about LS. To summarise: there is no consensus on the interpretation of ‘understandable language’.

During our research, we spoke to the authorities responsible for monitoring compliance with the Directive by public websites across 16 German states as well as the federal government. We also developed technical tools to automatically evaluate the complexity of web page content across .de domains.

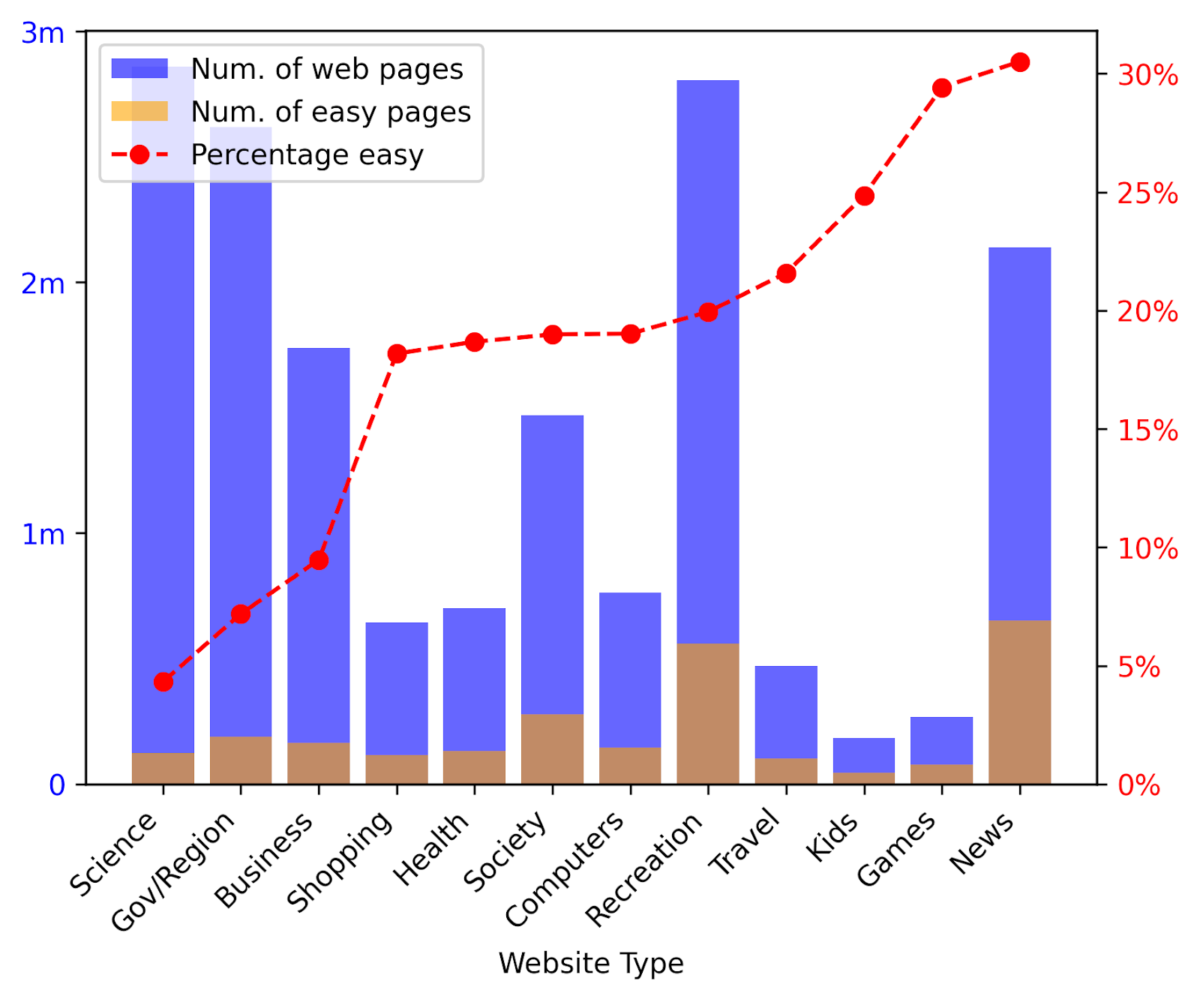

Science & governmental websites use difficult language

We trained a neural classifier to detect simple language and ran it on the German subset of the Common Crawl, one of the best open archives of the web. We then looked at the categories of the web content that our classifier said were “simple”: science and governmental websites had the lowest proportion of easy-to-read pages, whereas the categories kids, games and news had the highest.

Quality of LS is good, but its coverage not so

There are no legal requirements regarding the amount of LS a website must have. Our conversations with the public monitoring offices confirmed that they merely check for the existence of one page in LS. We collated a list of public sector websites from different German states, crawled them, and found 2,413 LS pages. We analysed the quality of these pages and found that generally, the quality of the pages in LS was high. This was perhaps not surprising as the responsible offices told us that the vast majority of LS texts are written by specialist translation agencies (and often verified by users of LS). However, of the websites in our sample, just a third had content in LS, and only 40 sites had more than three pages in LS.

Estimating LS usage is difficult

We also asked if there was any information on how the LS content is being used. We received some limited information on page impressions. Page impressions are not a reliable indicator of usage by themselves; nonetheless, for the statistics that we received, large differences in impressions were noticeable. This might indicate that some content has more priority for the target groups of LS. For example, Berlin’s waste collection and public transportation services both reported fairly high page impressions, indicating their relevance.

The glass is half empty…

We recommend that all monitoring bodies release the list of websites that are in their jurisdiction, including those that are selected for testing, publicly. At the moment, only a few of the federal states do this. This would open up the process of creating and monitoring LS content, allow a dialogue between public organisations and the potential target users, and hopefully place emphasis on the content that the target users need most. We also suggest that using LS to improve understandability should be combined with efforts to simplify the bureaucratic process in general, and striving to make all government communications and content more understandable—instead of offering only navigation and key information in LS.

The glass is half full

Having said this, even though the goal of a truly accessible web still appears far away, we think it’s fair to say that the EU Web Accessibility Directive has succeeded in at least two ways: all German states have monitoring offices set up, with competent personnel, and processes are in place so that LS pages can be created for the public sector at a reasonable price. In other words, the Directive’s objectives of shifting the burden of monitoring accessibility to the public authorities, and using their procurement powers to incentivize suppliers, seem to be working, although perhaps at a slower pace than one would hope.

More details can be found in our paper and our code can be found on GitHub.

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Artificial intelligence and society

The Human in the Loop in automated credit lending – Human expertise for greater fairness

How fair is automated credit lending? Where is human expertise essential?

Impactful by design: For digital entrepreneurs driven to create positive societal impact

How impact entrepreneurs can shape digital innovation to build technologies that create meaningful and lasting societal change.

Identifying bias, taking responsibility: Critical perspectives on AI and data quality in higher education

AI is changing higher education. This article explores the risks of bias and why we need a critical approach.