Making sense of our connected world

Public Interest Tech: A take on the actors’ perspectives on ecological sustainability

Ecological sustainability is a complex issue which also affects digital technologies. But how do stakeholders handle the situation? How important is ecological sustainability for them and what measures are they taking? In 2022, we at HIIG’s AI & Society Lab conducted the “Civic Coding” study for three federal ministries – the BMAS, BMUV and BMFSFJ – in which we investigated potentials and requirements for the public interest-oriented use of AI. As part of this qualitative survey, we also asked various actors how they handle ecological sustainability in relation to AI.

Ecological Sustainability – What are we talking about?

The United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development described sustainable development in the 1987 Brundtland Report as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future populations to meet their needs. For a full assessment of the sustainability of a decision, the three dimensions of ecological, social and economic sustainability must be considered. Here, however, I focus on ecological sustainability. Decisions affect ecological sustainability when they have an impact on natural resources and planetary boundaries.

In terms of digitalisation, this often means quantifying energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions through digital technologies in order to devise saving mechanisms. For example, Lynn Kaack et. al. estimate that GHG emissions from the information and communication technology (ICT) sector account for about 1.4% of global GHG emissions, a fraction of which is caused by AI applications. Their share – as well as the GHG emissions of the ICT sector as a whole – could increase in the future, for example due to increased use. At the same time, a difference can be made by increasing the efficiency of hardware, using renewable energy and using appropriate software. Other dimensions, such as ecosystem degradation or resource scarcity, are addressed much less frequently. Obviously, ecological sustainability is definitely relevant for AI and the ICT sector.

What do the actors interviewed know and do?

Among the actors we interviewed about ecological sustainability were representatives of ten projects that partly use AI as a technology, four networking organisations, one funding organisation, one educational institution and two actors from the tech activist sector. We wanted to find out how important the ecological effects of digital technologies are for the respondents, what measures they take and what prevents them from doing so, should they not do so. The results showed that the ecological effects of digital technologies are given high relevance: for 13 of the 18 respondents, this is an important issue. Considering that the debate on sustainable AI is still relatively young, this is astonishing, especially since some of the respondents are civil organisations with limited resources.

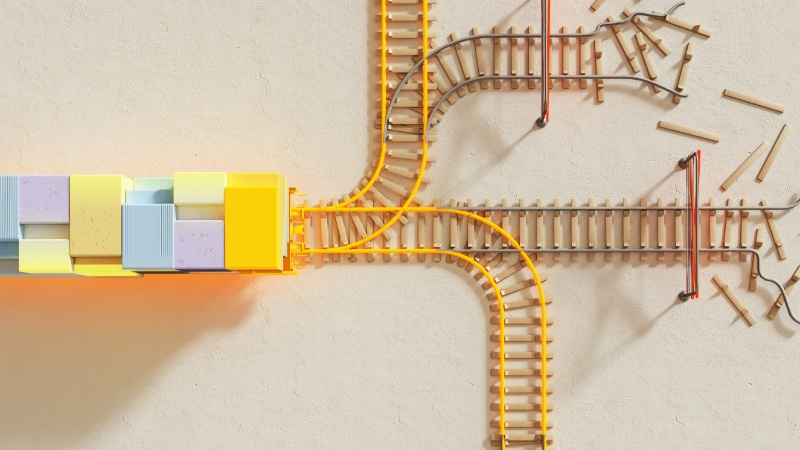

The figure above shows the composition of the respondents for the Civic Coding study: ten representatives of concrete tech projects, four networking organisations, one funding organisation, one educational institution, two actors from the tech-activist sector, additional two experts were not asked about ecological sustainability. Representatives of 13 of these 18 organisations indicated that ecological sustainability of digital technologies is an important issue, represented by the coloured boxes. At the same time, the representatives of 5 of the 18 organisations indicated that sustainability of digital technologies does not play a major role in their organisation, represented by the grey fields. However, only a small proportion, namely eight of the 18 respondents, take action despite the fact that the issue of ecological sustainability is considered so relevant.

This figure shows the actors who take measures to minimise the ecological effects of their applications or encourage other actors to do so. This is the case for the coloured fields, but not for the grey ones. Concrete measures are taken by four of the projects, one of the networking organisations, one funding organisation, one educational organisation and one of the organisations from the tech activist sector. The measures mentioned by the respondents ranged from adapted funding guidelines, which can include an appropriate model size or reusability, to educational offers on the ecological impacts of AI applications and the choice of energy sources.

This figure shows which measures were taken by which actors. In part, the measures taken are specific to the respondent’s field of activity and not all measures are possible for all respondents. Also, some planned to take measures in the future. Nevertheless, the question arises: Why are specific measures only taken by a relatively small proportion of respondents?

Reasons for lack of action regarding measures for ecological sustainability

The respondents named several obstacles: on the one hand, a lack of expertise to assess which decisions are significant. On the other hand, the tech landscape is dominated by a few large players, which creates dependencies on “common providers” by requiring high computing power. Here, new knowledge could be generated or access to existing knowledge could be simplified through networking of actors. Additionally, the collection and transfer of knowledge on concrete decisions in relation to AI and ecological sustainability might help. This is because the respondents each took only individual measures and could therefore learn from the additional measures taken by others.

Conclusion

Although our Civic Coding survey is not representative, it provides important insights and allows for follow-up questions to be asked: Can it be confirmed that environmental sustainability is given high importance in the field of public interest-oriented AI and technology? Are there actually few measures being taken? Which actors can take which measures? Which measures have which effects? Are there differences by sector, funding or size of actors? And what could help to make it easier for actors to take action?

Now it is important to at least bring the existing scientific knowledge to the actors as concrete possibilities and perspectives for action. The development of sustainability criteria for AI or transparency measures such as the Blaue Engel for data centres are a great step forward. It is important to do this in consultation with stakeholders to ensure the actual usability of these offers. At the same time, it must be clear: Even if actors are highly interested in ecological sustainability, it must be made structurally easier for them to achieve it so that relevant measures are actually getting implemented.

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Artificial intelligence and society

The Human in the Loop in automated credit lending – Human expertise for greater fairness

How fair is automated credit lending? Where is human expertise essential?

Impactful by design: For digital entrepreneurs driven to create positive societal impact

How impact entrepreneurs can shape digital innovation to build technologies that create meaningful and lasting societal change.

Identifying bias, taking responsibility: Critical perspectives on AI and data quality in higher education

AI is changing higher education. This article explores the risks of bias and why we need a critical approach.