Making sense of our connected world

Why we think Wall-E is cute and fortune teller robots are creepy

Have you ever noticed that some robots look super cute while others look incredibly creepy? Imagine, for example, Wall-E of the same-titled movie: Eyes that look like binoculars, no face, box-shaped body, and clamps for hands. While that sounds scary at first, the robot is a loveable character and generates almost instant empathy.

ever noticed that some robots look super cute while others look incredibly creepy? Imagine, for example, Wall-E of the same-titled movie: Eyes that look like binoculars, no face, box-shaped body, and clamps for hands. While that sounds scary at first, the robot is a loveable character and generates almost instant empathy.

And now imagine one of these fortune teller robots th at sit behind a pane and, from a distance, almost look like a real person. But the closer you get, the more you feel some sort of stranger anxiety. Something feels off—this almost life-like robot creates not empathy but distress and an eerie and weird feeling.

at sit behind a pane and, from a distance, almost look like a real person. But the closer you get, the more you feel some sort of stranger anxiety. Something feels off—this almost life-like robot creates not empathy but distress and an eerie and weird feeling.

Why? It’s a phenomenon called the uncanny valley effect. Even though Wall-E is much more unfamiliar to us and we’ve probably never seen anything like it, we still connect and relate better to an un-human robot than to an almost human-like robot. In fact, we’re repelled by machines that almost look and behave like humans but exhibit subtle queues that they’re not human.

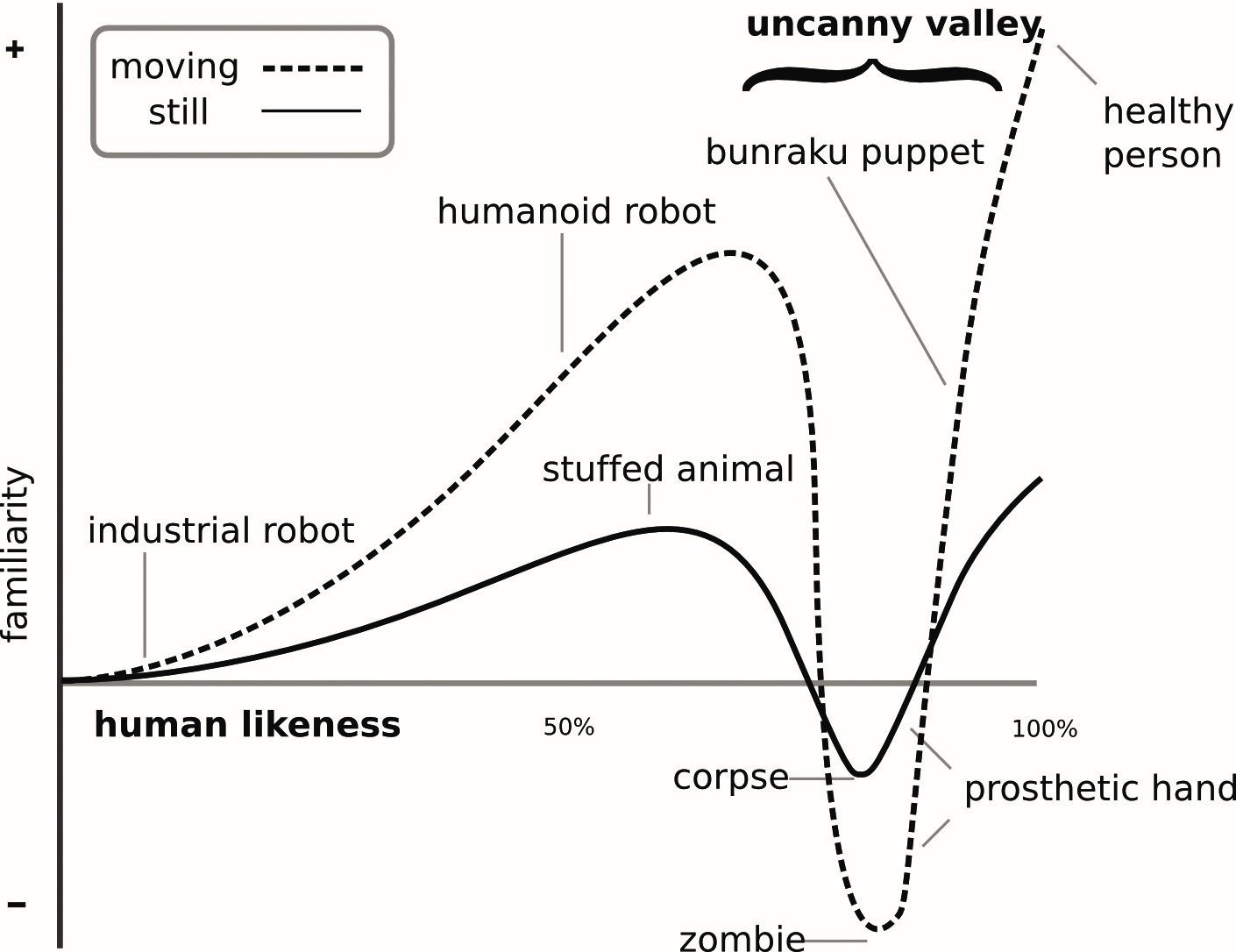

Let’s take a closer look at the uncanny valley. Termed by Japanese designer and roboticist Masahiro Mori in his 1970 article, Bukimi no Tani Gensho, Mori referred to Freud’s concept of uncanniness (Unheimlichkeit). In essence, it describes a growing feeling of unease when animated objects become more similar to real ones. Interestingly, before the graph dips, familiarity and empathy steadily increase with human resemblance. The comfort level then drops rapidly as human-likeness reaches a specific point, arrives at a maximum of perceived uncanniness, and then steeply rises again soon after.

Mori and researchers following his path came up with multiple explanations of the uncanny valley. Some argue that humans developed an elaborate set of skills to spot defects in potential mates. Robots that are stuck in the uncanny valley oftentimes move in a slightly weird way, respond with a noticeable lag, or have an unnatural skin color. This creates the impression that something is wrong with this humanoid and that it’s either caused by disease or, you know, death. Most humans are strongly and deeply repelled by both. Another possible explanation for the robot eeriness we sometimes feel is that we expect too much. When an almost perfectly human-looking robot is presented to us, we expect that all its observable features measure up to human features. If, however, something is missing—eyebrows and fingernails for example—eeriness ensues. This notion is closely connected to an aversion to cognitive dissonance. Our minds are desperate to place a robot created to imitate human appearance in a mental category: human or robot. The more we struggle to choose the adequate category for the robot, the more uneasy we feel about it (Burleigh et al., 2013; Mathur & Reichlin, 2016).

For designers and their robots the question is, of course: How do you get out of the valley? For one, robots can prominently feature decision supports for humans—such as clearly robotic elements that move the machine left out of the valley. Coherence also benefits a positive appraisal of the robot. Mixing humanoid and robotic features, however, or featuring different levels of human-likeness confuse us. Machines that look like humans but move like a machine will likely end up in the uncanny valley. (Walters, 2008) Another strategy might seem odd at first, but has proven to be quite effective: Robots that take up elements and features of things that comfort us humans can move out of the valley to the right. Levels of familiarity, empathy, and affection can even match the levels we feel for other healthy human beings. While Mori’s 1970s article stated that “[o]f course, human beings themselves lie at the final goal of robotics, which is why we make an effort to build humanlike robots” he changed his mind a decade later: In 1981, Mori described the Buddha’s appearance—detached from worldly concerns, calm, and in a quiescent state—as utterly comforting to humans. Features of this kind might, in future, result in robots that evoke such deep affection in us that it even surpasses the level of familiarity we feel for fellow humans.

tl;dr: Robots that are not perfectly resembling humans, but try to, are creepy. They should either stop trying so hard and embrace their robot features or specifically include comforting, Buddha-like features.

This post is part of a weekly series of articles by doctoral canditates of the Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society. It does not necessarily represent the view of the Institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and asssociated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

Sources

- Burleigh, T. J., Schoenherr, J. R., & Lacroix, G. L. (2013). Does the uncanny valley exist? An empirical test of the relationship between eeriness and the human likeness of digitally created faces. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 759-771.

- Mathur, M. B., & Reichling, D. B. (2016). Navigating a social world with robot partners: A quantitative cartography of the Uncanny Valley. Cognition, 146, 22-32.

- Mori, M. (1970). The Uncanny Valley. Energy, 7(4), 33-35.

- Mori, M. (1981). The Buddha in the robot. Kosei Publishing Company.

- Walters, M. L., Syrdal, D. S., Dautenhahn, K., Te Boekhorst, R., & Koay, K. L. (2008). Avoiding the uncanny valley: robot appearance, personality and consistency of behavior in an attention-seeking home scenario for a robot companion. Autonomous Robots, 24(2), 159-178.

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Digital future of the workplace

Online echoes: the Tagesschau in Einfacher Sprache

How is the Tagesschau in Einfacher Sprache perceived? This analysis of Reddit comments reveals how the new simplified format news is discussed online.

Opportunities to combat loneliness: How care facilities are connecting neighborhoods

Can digital tools help combat loneliness in old age? Care facilities are rethinking their role as inclusive, connected places in the community.

Unwillingly naked: How deepfake pornography intensifies sexualised violence against women

Deepfake pornography uses AI to create fake nude images without consent, primarily targeting women. Learn how it amplifies inequality and what must change.