Making sense of our connected world

The politics behind the Smart City

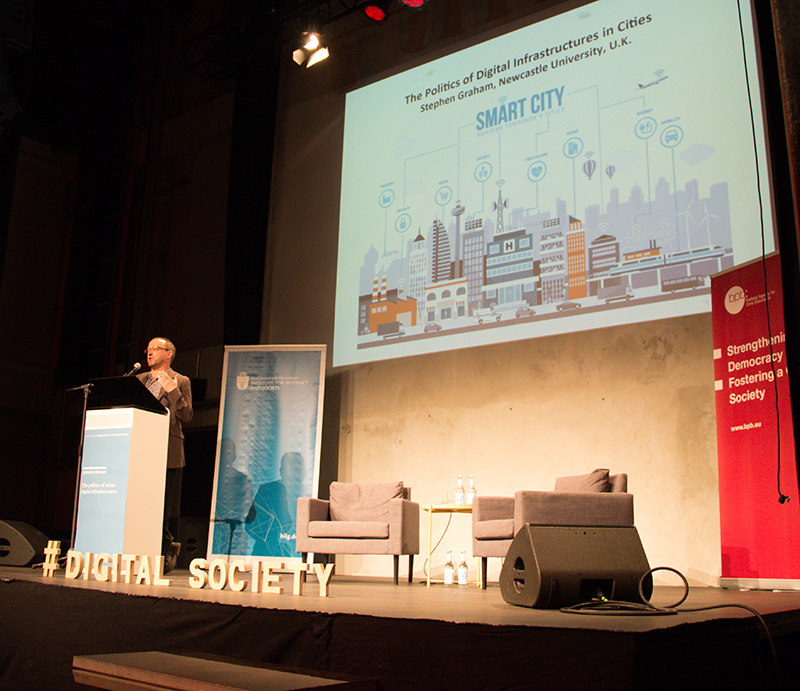

Modern cities depend largely on invisible infrastructures. The much-hyped ‘Smart Cities’ promise to digitise the urban – but what happens when they fail? How do we make sure that cities in the digital society remain public spaces? How can they be designed to foster the public good and not just commercial interests? On 24 September, Stephen Graham continued the lecture series Making Sense of the Digital Society. In this article, Marc Pirogan takes a look on Graham’s lecture on ‘The politics of urban digital infrastructures’.

To begin his lecture, Graham emphasised that infrastructure helps to transform nature into culture. It brings resources from the hinterlands to the cities and helps to relocate the output and waste that is being produced in cities. The webs of infrastructure of food, logistics, energy, waste, information and so on are often invisible, but without them life would break down immediately.

Infrastructure is something that is often spoken about, but is rarely defined. Building on Susan Leigh Star, Graham listed several characteristics of infrastructure that help to gain a better understanding what it entails. Infrastructure offers spatial and temporal reach, thereby compressing categories like space and time. People have to learn to use it and it is also linked to conventions of practice, as culture and social norms play an important role. Furthermore, infrastructure embodies standards, which becomes visible, for instance, in different national standards for electricity plugs. It is also always incorporated in the world around us and usually built in modular increments.

It is often forgotten that infrastructure is embedded in other aspects of life and facilitates them. Infrastructure is transparent in the sense that you don’t need to understand all the complex processes in order to use it. Therefore, scientists often speak of the black-boxing of technology. Another important aspect of infrastructure is that it tends to be only visible when it breaks down. For instance, a fire in a railway tunnel in Baltimore in 2001 that affected fiber cables caused a lack of e-mail access in many African countries. This materiality is something that is often forgotten.

With regard to digital infrastructure, Graham noted that it consists of huge server farms that consume lots of energy. This is why they are being moved further and further to the north of the globe, where the enormous cooling systems work better. This backstage area of the digital and virtual is very important to bear in mind, because it has enormous environmental effects. The question of infrastructure is therefore not just a technical one, but also a very political one.

Nowadays, we live in a society where digital infrastructure is mediating almost everything. Contrary to former assumptions, digitisation has not stopped processes of increasing urbanisation. Between the 1960s and 1980s many scientists assumed that cities would cease to exist because of the rising capacity to process and transmit information. Because of this time-space compression, they argued that space would become less important. Graham’s argument, in contrast, is that digital media and technologies facilitate urbanisation. Place still matters, maybe more than ever. Rather than substituting for existing infrastructure and technologies, they become remediated through digitisation. Places are reorganised and reanimated, and so are cities as a whole.

Upcoming lecture: Nick Couldry on data colonialism

Concerning cities, Graham also shed light on the concept of the smart city, which has become very dominant in recent times. This futuristic term is mainly used for marketing purposes by technology companies and real estate organisations, but also municipal authorities. The notion of the smart city is actually a cybernetic idea, which implies that information allows us to gain perfect control over the life in a city. Cybernetic concepts have already existed since the 1940s and despite all previous failures, the dominant actors argue that now through new technologies and infrastructures such as ubiquitous computing, pervasive sensors and the internet of things, perfect control will be possible.

Technology companies such as IBM are offering systems and services that allow city authorities to connect separate domains centrally in real-time. Cities, on the other hand, are trying to sell themselves as innovative hubs, which gives them symbolic power and attracts capital. Moreover, these futuristic notions of technological progress and efficiency are combined with an ecological narrative and promise. Graham noted that what is often lacking in these concepts are people and the social dimension of a city. Therefore, he described the smart city as a technocratic and elitist imaginary.

If cities are organised as a vast array of software, software also becomes the city’s source of agency. The politics of the city is then determined by who writes the software. This is often invisible and orchestrated in a way that is hard to counter by political mobilisation, activism, and regulation. Pervasive video cameras and software analytics are not linked to responsible individuals and so the programmer of software has the power to shape the right to the city.

Instead of the asocial and technocratic logic of the smart city, Graham proposed a social vision of the future of cities. These visions need to start with all the social, political, and environmental concerns cities and people living in them are facing. Digital technologies and infrastructure can be part of a solution for urban struggles, but should not be seen as an all-encompassing remedy.

Selected Tweets

Getting more #data on the situation in #cities such as Rio doesn’t necessarily improve the situation – broader social change required #digitalsociety

— BuzzingCities Lab (@BuzzingCities) 24. September 2018

Stephen Graham: Most #SmartCity visions focus on more data capture and not on the social and ecological problems of todays cities. #digitalsociety #dataextractivism #surveillancecapitalism pic.twitter.com/BFYiMsR6Nr

— Patrick Stary (@p_stary) 24. September 2018

Stephen Graham’s remarks remind me of what @PopTechWorks shows in “Automating Inequality”: Tech solutions can camouflage problems they are designed to solve. You might have more data about the problem, but politics remain. #digitalsociety

— Uta Meier-Hahn (@zielwasser) 24. September 2018

Stephen Graham is Professor of Cities and Society at Newcastle University’s School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape. He has an interdisciplinary background linking human geography, urbanism and the sociology of technology. Since the early 1990s he has used this foundation to develop critical perspectives addressing how cities are being transformed through remarkable changes in infrastructure, mobility, digital media, surveillance, security, militarism and verticality. The lecture series Making Sense of the Digital Society will continue on 20 November 2018 with Nick Couldry. If you want to stay up to date, subscribe to our event newsletter here.

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Platform governance

Polished yet impersonal: The unintended consequences of writing your emails with AI

AI-written emails can save workers time and improve clarity – but are we losing connection, nuance, and communication skills in the process?

AI at the microphone: The voice of the future?

From synthesising voices and generating entire episodes, AI is transforming digital audio. Explore the opportunities and challenges of AI at the microphone.

Do Community Notes have a party preference?

This article explores whether Community Notes effectively combat disinformation or mirror political biases, analysing distribution and rating patterns.