Making sense of our connected world

When Online Research Can Do Harm

While research ethics are a core component to all social research, digital ethnography poses an additional set of unique challenges that must be addressed while researching vulnerable populations, but still advice for digital ethnographers[1] in terms of the ethical dilemmas of researching and marketing to vulnerable populations online is scarce. The aim here is not to create ethical protocols or standard prescriptive as to how digital ethnographers should practice ethnography online, but to discuss some ethical considerations and challenges associated with researching vulnerable populations, in hope to sensitize social researchers to the potential issues digital ethnography poses.

Vulnerable groups, who are they?

When we hear the word ‘vulnerable’, we might think of economically disadvantaged people, racial and ethnic minorities, children, teenagers, or disabled people, and that’s all correct. If we check definitions among extant literature, we will figure out that vulnerable groups are individuals who are at greater risk of poor physical and social health status (Rukmana, 2014), where vulnerability can either be perceived as a situational, short-run phenomenon, or a more enduring, even permanent state (Mansfield & Pinto, 2008). Vulnerable groups experience disparities in physical, economic, and social health status when compared with the dominant population (Rukmana, 2014). From a consumer perspective, consumer vulnerability is concerned with the potential risks and social consequences populations or individuals face in different consumption contexts (Baker, Gentry, & Rittenburg, 2005).

Could we possibly harm vulnerable groups in online research, unwittingly?

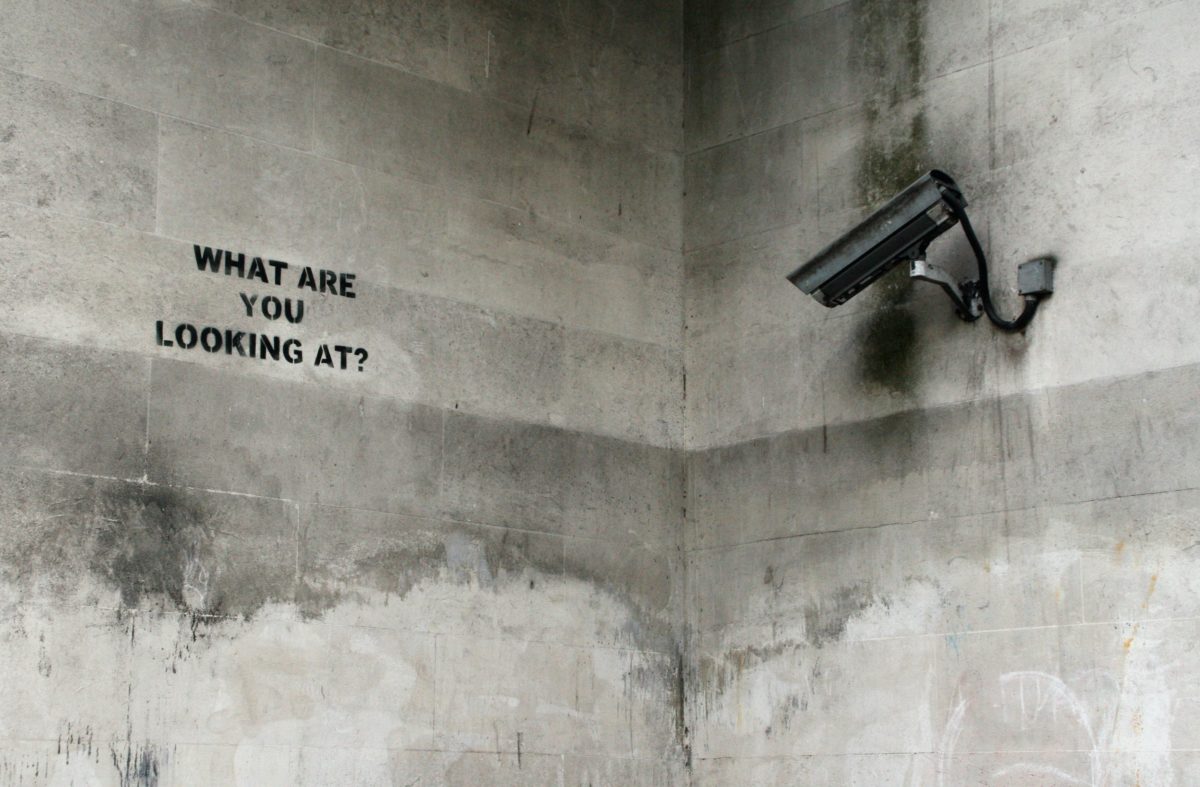

Harming vulnerable groups could occur unwittingly while researching them online. Rule number one is to ensure that the researched participants (the vulnerable populations) are empowered in their own representations, and given agency in their interactions with researchers. An inherent challenge in maintaining this relationship in a digital age is that data representation may have unintended outcomes beyond the control of individual researchers and their participants. For example, the identification of textual data in a research output can mean that specific individuals can be traced. Visual data representations can pinpoint specific geographical areas. Researching vulnerable populations requires that special attention to be paid to the design of the studies, and to the collection and dissemination of data. Protection of rights, wellbeing, safety, privacy and confidentiality are all crucial elements that we must prioritize while researching vulnerable communities, to avoid bringing these vulnerable individuals into disrepute, endangering them within their social fabric, where they are already disadvantaged (Shivayogi, 2013).

Not one layer of vulnerability, actually two

All of us experience online vulnerability, whether we would be deemed a ‘vulnerable’ individual or not. Our daily online practices potentially make us vulnerable, with privacy risks posed by sharing not only personal information but the generation of any information that distinguishes one person from another, such as usage, or sharing data that ties a device ID to a person, which could be used for “re-identifying anonymous data” (Politou et al., 2018: 3). These unconscious online practices might expose users to a variety of online vulnerabilities such as data misuse, identity theft, online harassment, and exposure to inappropriate content (Boyd & Ellison, 2008). Online vulnerability is complex. There are also psychological and social benefits to engaging online, in terms of social connectivity, self-esteem, and support (Burke & Kraut, 2016). Another layer of vulnerability emerges when individuals are themselves vulnerable.

Teenagers, for example, comprise a vulnerable group which has been researched extensively. A research overviews 400 studies across Europe and reveal five in ten teenagers have given away personal information, four in ten have witnessed online pornography, three in ten have seen violent content, two in ten have been victim to bullying, and one in ten has met someone first encountered online (Livingstone and Haddon, 2009).

Similar risks of harm could be considered with other groups online, such as the bereaved, repressed, abused, depressed, and stigmatized, who may use digital self-presentation and social interaction as a coping mechanism for self-transformation, but experience vulnerability and disempowerment (Baker et al., 2005). This broader understanding of online vulnerability and how vulnerability could be aggravated online warns us of the importance of digital research ethics in light of online vulnerability. Therefore, we will discuss some core ethical considerations which sensitize social researchers to some of the ethical challenges associated with digital research on vulnerable individuals.

Researcher transparency: not too passive, not too strict

There is no prescription that details how digital ethnographers can actively declare their identities and research interests to the participants that they are studying, although various ways of dealing with this issue in the digital realm have been suggested (Costello et al., 2017; Yeow, Johnson, & Faraj, 2006). On the one hand, researchers may disclose his or her presence, inform participants about the research, and consistently and overtly interact with informants (Murthy, 2008). Yet even in cases where the ethnographer is virtually present, the speed and the volume of postings within a thread of conversation can quickly cause the role of the researcher to recede into the background. If this happens, researchers may run the risk of falling into a covert research role in order to collect data, a subject position that exemplifies ‘lurking’. Lurking on the web refers to the epistemic position of a researcher who passively watches web interaction unfold without interacting in the setting, which creates a perception of privacy, as participants are often only cognizant of the people with whom they are actively interacting (Barnes, 2004).

On the other hand, if researchers do interact, they become organizing elements of these online spaces, co-constructing the informant with whom they are interacting, contributing to the development of their identity, and creating the field in which the study occurs. This co-construction of space immerses both the researcher and the research participants in guiding the topic of conversation and the nature of the dialogue. Therefore, you don’t want to be too strict in adhering to your transparency, as it disrupts the flow of interaction, neither do you want to be too in declaring your research position, as you run the risk of unethically exploiting your participants. Therefore, the advice here to reconcile this confusing position through what so called ‘self-reflexivity’.

Avoid ‘going native’ and keep your ‘self-reflexivity’ button on

Reflexivity is constantly needed to avoid the risk of ‘going native’, and maintaining a critical distance from the participants and their stories. Researcher self-reflexivity towards their relation to the research object is another key ethical consideration. A call for self-reflexivity is a call to acknowledge the way in which the researcher’s knowledge about the world influences research claims, and to acknowledge what the researcher brings with them in terms of personal and social biases to the object of inquiry. Employing reflexivity as a ‘sensitizing device’ empowers the researchers’ decision making with regard to the field study, what is considered to be meaningful data, and how ethically to represent the lived experiences of the studied subjects (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992).

Data collection, then fabrication

Researching some vulnerable communities in political sites where researchers could potentially bring political activists under the spotlight and disclosing the dynamics of activism might expose participants to surveillance, repression, and personal threats. A fieldwork encounter that highlighted this tension was doctoral research by the author exploring politically motivated social movements in Palestine (Nazzal, 2017). In Palestine, a country which has experienced considerable political turbulence, from Israeli occupation and state authoritarianism, the dangers of inadvertently exposing the identities of activists is readily apparent. In addition, the web affords a higher degree of visibility (Ebo, 1998), which might facilitate the tracking of the participants’ online identities and relationships. So what can we do?

Some scholars draw attention to the importance of data triangulation, and the potential for researchers to collect netnographic data that misrepresents vulnerable groups. Therefore, it is important to verify social media data through private social media channels and offline interactions. Moreover, researchers also advocate data fabrication to protect informants’ identities (Markham, 2012). Scholars may need to create a composite dialogue through paraphrasing the participants’ quotations, paying careful attention to changing details of the data, and the social media platform, to assure participants’ confidentiality and privacy. Therefore, participants’ confidentiality, privacy, and anonymity must be given highest priority.

Data representation: hide or represent?

While conducting netnographic research, the researcher needs to think about data representation. First, digital ethnographers should evaluate what is considered meaningful data, what is to be excluded, and how data can be filtered into appropriate categories for interpretation and analysis. Reflexivity on the data collected, and the way it is presented, should be one of the major ethical considerations as the researcher filters data based on critical reflection and ethical research standards.

There needs to be sensitivity from the researcher to the fact that ‘every choice we make about how to represent the self, the participants, and the cultural context under study contributes to how these are understood, framed, and responded to by readers, future students, policy makers, and the like’ (Markham, 2005: 811). For example, data collected from Palestine warns the author (Nazzal, 2017) to exclude some of the collected data as conditions of online surveillance and punitive action had worsened, where new laws and legislation were introduced by the Palestinian state to reinforce control and mass surveillance over of Palestinian social media accounts. For example, The researcher found evidence of ‘digital occupation’ where Israeli forces arrested more than 300 Palestinians from the West Bank in 2017 because of social media posts (The Arab Center for the Advancement of Social Media reported – 2018).

At the end, more attention to the need for ethical protocols, signaling existing perspectives with a particular eye on vulnerable consumers and advocating safeguards needs to be considered from academics, policy makers, marketers and individuals.

[1] Digital ethnography is an online research method that adapts ethnographic methods to the study of the communities and cultures created through computer-mediated social interaction (Murthy, 2008).

Amal Nazzal is an Assistant Professor at the Birzeit University at the Faculty of Business and Economics.

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Featured Topics

The bot that bit back: AI agents, defamation and the digital construction of identity

A real case of an AI agent publishing a smear piece raises new legal questions about responsibility and digital identity.

The Human in the Loop in automated credit lending – Human expertise for greater fairness

How fair is automated credit lending? Where is human expertise essential?

Impactful by design: For digital entrepreneurs driven to create positive societal impact

How impact entrepreneurs can shape digital innovation to build technologies that create meaningful and lasting societal change.