Unsere vernetzte Welt verstehen

Fotos, Parodien und das Urheberrecht

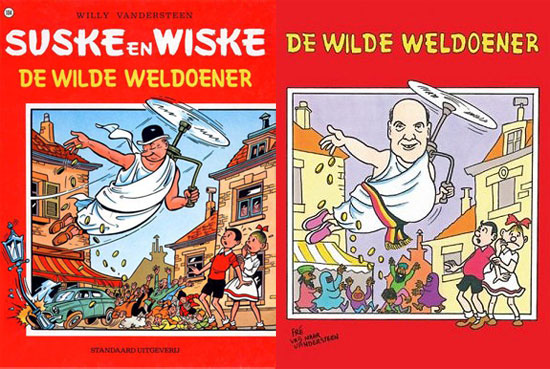

Darf ich ein fremdes Foto digital stark verändern, um es etwa für einen Fotowettbewerb einzureichen? Oder verletze ich damit das Urheberrecht des Fotografen ? In Deutschland kommt es für die Antwort dieser Fragen darauf an, ob die Weiterverwendung als sogenannte freie Benutzung gelten kann. Sollen die Änderungen jedoch eine Parodie darstellen, müssen auch Vorgaben des europäischen Urheberrechts beachtet werden. Eine Entscheidung des BGH zeigt, wie nationale Gerichte künftig mit Parodien und (EU-)Urheberrecht umgehen werden.

Recently, the German Federal Court of Justice published a decision in a case concerning the parody of a photograph. This decision is remarkable, because it is the first one since the CJEU’s Deckmyn decision on the EU exception for parodies (Art. 5(3)(k) InfoSoc Directive). In Germany, a parody is lawful, if it meets the general requirements of free use, which is stipulated in Article 24 of the German Copyright Act (GCA). The CJEU’s 2014 decision in Deckmyn, however, established that parody is an autonomous concept of EU law and must thus be interpreted uniformly throughout the EU.

The definition of parody that the CJEU gave has not exactly aligned with the requirements of free use as established by German courts over time. A lot of issues around parodies thus remained unclear after the CJEU decision. Because Germany doesn’t have a proper exception for parodies, but allows them as part of free use – would German courts even (have to) follow the CJEU definition? Also, the CJEU definition of a lawful parody was criticized for being too broad and too narrow at the same time and for taking into consideration interests that, under German law, traditionally concern moral rights. European law does (or should?) not harmonize moral rights and it was uncertain how German courts would fit the CJEU parody definition into the German copyright system.

The CJEU’s definition of parody in Deckmyn

But let’s back up and start with a quick look at what exactly the CJEU decided in Deckmyn. Most importantly, the Court declared that a parody under Art. 5(3)(k)InfoSoc directive only has to meet two conditions: “first, to evoke an existing work while being noticeably different from it, and, secondly, to constitute an expression of humour or mockery”.

The Court then went on to explain that it is necessary to strike a fair balance between “the interests and rights” of the rights holders on the one hand, and “the freedom of expression of the user of a protected work” on the other hand. This, according to the CJEU, requires national courts to take “all the circumstances of the case” into account and decide whether a fair balance is struck or whether the rights holder has a legitimate interest in prohibiting the use of his work for the parody. Because the case at hand in Deckmyn concerned a potentially racist message, the CJEU referred to the principle of non-discrimination based on race, colour and ethnic origin (which was defined in another European directive that is not related to copyright) and hinted that this may be a case where the rights holder has a legitimate interest to forbid the parodist’s use of his work.

Why the Deckmyn decision raised some concerns

For one, some commentators were worried that the CJEU parody definition was too broad because a parodist does not have to make a statement about the work that he uses but can basically use any work to make a joke about something entirely different. The concern was that this could possibly allow him to exploit unfairly the work of someone else without adding much creativity.

Most importantly, some critics were concerned that the CJEU effectively asks national courts to inspect the content of the parodist’s message for political correctness. This appeared worrisome, because copyright law is not supposed to be an instrument to censor silly, offensive, untruthful or similarly unwanted messages so long as the new use does not infringe the copyright holder’s moral rights (which remain unharmonised at the EU level).

How the German Federal Court incorporated the EU definition of parody

The case before the German Federal Court concerned a photograph of an actress that someone changed in such a way that the person in the photo appeared to be overweight. All this had happened for an online contest – “Promis auf fett getrimmt” – that asked participants to change photos of celebrities to make them “look fat”.

The photographer sued a news website that reported about the contest and showed the manipulated photograph, because he claimed that his copyright had been infringed. The defendant argued that the altered photograph constituted a free use of the original work (in form of a parody). The case was thus an opportunity for the German Federal Court to clarify how to handle parodies after the CJEU Dekcmyn decision. These are the main takeaways:

Even though free use covers more types of uses than parodies and is considered by many scholars to be an inherent limitation of copyright rather than an exception, the Federal Court argued convincingly that the way German courts handle parodies has the same effects that a proper parody exception would have. EU law is thus applicable to Art. 24 German Copyright Act insofar as it relates to parodies.

The Court changed its jurisprudence on parodies to adopt the EU definition. It gave up the requirement that the parodic use must constitute an original (copyright protected) work (para 28). It also let go of the condition that the parody must subvert the meaning of the original work and make a (likely critical) comment about the original work itself (para 34). The Court thus found that the new picture fulfilled the CJEU definition of a parody, being noticeably different while still evoking the original work and also mocking the portrayal of celebrities in the media.

Especially interesting is the way the Court dealt with the balancing of different interests.

First, it considered that the fact that the new use is a distortion of the original work (Art. 14 GCA) supports the original photographer’s case (para 38). Thus, the Court explicitly (and, for a national court convincingly) considered moral rights.

Second, it found that the parodist’s free speech argument would have been stronger had he made a direct comment about the original work itself. In a way, the Court thus reintroduced its former free use parody requirement via the balancing of interests. In this case (the court here drew upon the lower court’s analysis) the parody only used the original work to make a broader, implicit comment about the sexualized portrayal of women in today’s media (paras 35, 38). Thus, freedom of expression would have merited more profound consideration for the parodist, if he had criticized the original photograph itself (it remains a little unclear how that could have been achieved).

Third, the Court investigated whether the rights of third parties that lie outside of copyright law may have been infringed by the parody, and whether the rights holder might have a legitimate interest in not being associated with the use. However, the court also stressed that freedom of expression is essential for the good of society and that the balancing of interests must not be confused with a general “political-correctness-control” (para 39). The photographer could only have a legitimate interest in not being associated with possible personality rights violations of the actress, if the manipulation of the photograph had been hidden. Interestingly, the question whether the message of the new use can reasonably only be attributed to someone other than the author of the original work is another aspect of the traditional free use test that the court managed to keep through the balancing of interests.

The Federal Court did not end up deciding whether the balancing of interests should lead to the parody being unlawful or not, but referred back to the lower court that previously had incorrectly applied the old(national) free use test. Overall, the Federal Court embraced the EU definition of parody. At the same time, it made use of the leeway the CJEU left national courts to keep the parody exception close to the traditional free use test and thus implicitly addressed some of the concerns voiced by critics of the CJEU decision.

What next?

Likely, free use’s primary field of application are parodies, but it also allows other creative uses. For example, the German Constitutional Court recently decided that (under certain conditions) it may also allow the sampling of short snippets of music. This, of course, raises the question of whether certain applications of free use effectively serve as an exception that is not provided for in the EU Directives and is thus prohibited. The relationship between the German free use exception and EU copyright law will therefore likely remain a hot topic.

Cover Picture: Joe Gratz, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0

Dieser Beitrag spiegelt die Meinung der Autorinnen und Autoren und weder notwendigerweise noch ausschließlich die Meinung des Institutes wider. Für mehr Informationen zu den Inhalten dieser Beiträge und den assoziierten Forschungsprojekten kontaktieren Sie bitte info@hiig.de

Jetzt anmelden und die neuesten Blogartikel einmal im Monat per Newsletter erhalten.