Unsere vernetzte Welt verstehen

Organic Search: Wie Metaphern helfen, das Netz zu bewirtschaften

Tomaten, Äpfel und Brot können “organic”, also “natürlich” oder “bio” sein – aber Suchergebnisse? Anna Jobin und Malte Ziewitz beschäftigen sich in diesem Essay mit landwirtschaftlichen Metaphern im Suchmaschinenmarkt und mit der Frage, welche Auswirkungen das hat. Dieser Artikel ist Teil unserer Blog-Serie Wie Metaphern die digitale Gesellschaft gestalten.

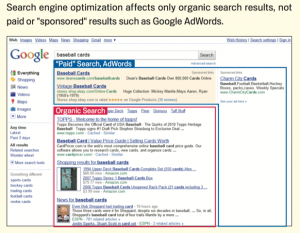

Do you prefer your search results ‘organic’? What may sound funny to the rest of us has long been a concern for search engine professionals around the world. Already the 2010 version of Google’s own Search Engine Optimization Starter Guide called those ten blue links usually associated with search results ‘organic’ – everything else was ‘paid’ or ‘sponsored’ (Fig. 1).

Interestingly, such agricultural metaphors are quite common when it comes to search. Hyperlinks are discussed as parts of the ‘ecology’ of Google products. Groups of websites linking to each other constitute ‘link farms.’ Links that have been built with the intention of improving rankings might be called out as ‘unnatural.’ And when links break and lead to nowhere over time, you’d better be concerned about ‘link rot.’

The imagery is intriguing, but it also raises some important questions. Neither links nor search results grow on trees and bushes. So what kind of work (or metaphorical service) do these metaphors do? How are they employed by those who use them on a daily basis, including users, search marketers, engineers, and Google representatives? To start answering these questions, let’s have a closer look at how – and for whom – search results become ‘organic.’

Dossier: Wie Metaphern die digitale Gesellschaft gestalten

Delineating marketable space

In their 1998 paper on ‘The Anatomy of a Large-scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine,’ Sergey Brin and Larry Page were careful to distinguish their proposal from ‘commercial’ and ‘advertising oriented’ engines. A key design goal, they wrote, was ‘to push more development and understanding into the academic realm’ and generate results based on the logic of citations rather than the preferences of advertisers. Twenty years later, it would be hard to see the engine as anything but commercial, generating $27.2 billion in advertising revenue in 2017 alone.

What has allowed the founders to stick to their original plan while also monetizing the technology is a distinction between two types of results: organic and non-organic ones. Not surprisingly, this distinction runs through corporate communications like a golden thread. According to Google’s advertising program AdWords, for example, an organic search result is a ‘free listing in Google Search that appears because it’s relevant to someone’s search terms.’ A non-organic search result, in contrast, is a paid advertisement. The selective invocation of ‘organic’ thus performs two kinds of links – those served by Google unilaterally and those served by Google on behalf of paying advertisers.

This differentiation provides the basis for a business model that depends on what economists have called a ‘two-sided market.’ Whereas users search for useful information, advertisers search for users. Although organic and non-organic links are produced in different ways, they both are triggered by the same query and appear on the same page. Calling some results ‘organic’ thus makes it possible for a company like Google to claim that they are not accepting money in exchange for influence while also generating revenue through ads displayed in those coveted first spots.

Regulating participation

In addition to making search results marketable, the distinction has further implications for all those who depend on being ranked and may seek to participate in the production of results. Depending on where and how they want to promote their websites, businesses, individuals, and organizations face some very different challenges.

For paid listings, an industry of pay-per-click (PPC) specialists helps webmasters run campaigns in non-organic search results. These professionals work with a wealth of tools and data to bid on ads to be displayed with search results for certain keywords. For organic listings, the situation is more complicated. In this case, an entire industry of search engine optimization (SEO) consultants offers webmasters to optimize their pages in order to rank ‘organically.’ Although their methods differ, both groups aim to appear high up on the results page for specific terms.

From the perspective of webmasters, then, the distinction helps to constitute two very different forms of intervention. As the officially sanctioned approach, PPC is accompanied by a sophisticated infrastructure of information and support, including dashboards, help forums, and analytics tools for individual advertisers. SEO, in contrast, operates in a moral grey zone. Although Google has issued some basic guidelines for designing websites, these tend to be generic and only selectively enforced. Not surprisingly, this ambiguity is difficult to navigate. Among other things, webmasters and marketers have to figure out what kind of changes to a website are permissible and thus ‘organic’– and what kind of changes do transgress into the realm of ‘un-organic’ manipulation.

Hiding in plain sight

Although metaphors like ‘organic’ play an important role in structuring the work of operators, webmasters, and marketers, it is important to remind ourselves that the implications are not obvious to everyone. In fact, research has shown that especially search engine users are generally not aware of the distinction between different kinds of links on the search results page. For example, a recent study at the Hamburg University of Applied Sciences suggests that, when asked to identify organic search results and ads on five different screenshots, ‘only 1.3 percent of participants’ are able to do so correctly. So even though the notion of ‘organic search’ makes perfect sense for marketers and operators, it does not have much currency with users.

This might not be an accident. In particular, it is interesting to see that, in stark contrast to the term’s prominence in search marketing materials, there is hardly any mention of ‘organic’ in user-facing communication. The company’s comprehensive guide on ‘How Search Works’, for example, uses ‘organic’ exactly once – ironically in a section that assures the reader that organic search results will always be generated independently from ‘clearly labeled’ advertising.

In other words, designating search results as ‘organic’ could – somewhat counter-intuitively – reinforce a belief in results as something ‘natural’ and given. For users, then, the business of web search is hiding in plain sight.

Cultivating the web

So where does this leave us? Technically speaking, the idea of distinguishing ‘organic’ from ‘non-organic’ results does not make much sense. Any search results page is a carefully constructed product of design and use. There is nothing inherently ‘organic’ about a list of computationally generated links. Nonetheless, the label has developed into something far beyond a mere description. As a metaphor, ‘organic search’ provides a focal point for ordering an entire field of social, economic, and political practice.

As social scientists, we have a rich set of tools at our hands to study how this work plays out in practice. How do these agricultural metaphors shape the lives and practices of users, analysts, and engineers? For whom do these distinctions hold and under what conditions? What would it take to undo them? In farming as in web search, making things organic takes an awful lot of work.

Anna Jobin is an International Research Scholar at Tufts University (USA) and an affiliate of the Health Ethics and Policy Lab at ETHZ (Switzerland). Her research is partly funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Malte Ziewitz is Assistant Professor at the Department for Science & Technology Studies at Cornell University (USA).

Dieser Beitrag spiegelt die Meinung der Autorinnen und Autoren und weder notwendigerweise noch ausschließlich die Meinung des Institutes wider. Für mehr Informationen zu den Inhalten dieser Beiträge und den assoziierten Forschungsprojekten kontaktieren Sie bitte info@hiig.de

Jetzt anmelden und die neuesten Blogartikel einmal im Monat per Newsletter erhalten.

Offene Hochschulbildung

Freundlich, aber distanziert: Die unbeabsichtigten Folgen KI-generierter E-Mails

KI-generierte E-Mails sparen Mitarbeitenden Zeit und erleichtern den Arbeitsalltag. Aber verlieren wir dadurch unsere Kommunikationsfähigkeiten?

KI am Mikrofon: Die Stimme der Zukunft?

Von synthetischen Stimmen bis hin zu automatisch erstellten Podcast-Folgen – KI am Mikrofon revolutioniert die Produktion digitaler Audioinhalte.

Haben Community Notes eine Parteipräferenz?

Dieser Artikel analysiert, ob Community Notes Desinformation eindämmen oder ob ihre Verteilung und Bewertung politische Tendenzen widerspiegeln.